Avant-Garde Women: Emmy Hennings, “Shining Star of the Voltaire”

The Greatest Cabaret in the History of the World

The Greatest Cabaret in the History of the World

It is criminal that Emmy Hennings’s books have not been translated from German to English after more than 100 years. She was arguably the founder of Dadaism in 1916, the most important art movement of the 20th century. To the press, she was unquestionably Dada’s tentpole performer. Dada — anarchic, nihilistic, and self-consciously weird — continues to inspire. All Hennings’s male contemporaries have translated books available, so what is the holdup? I’ll buy a German-English dictionary and do it myself if I have to. Her books run hundreds of pages so it will take me the rest of my life. But it’s not fair that German readers hog her work to themselves, especially with modern interest in the female Dadaists. The delay is perhaps explained by continual critical confusion over her true role. [UPDATE: A translation of her novel “Branded” has been released; here is my review.]

Hennings was a political radical and anti-war activist. She faced prison, morphine addiction, mental health issues, and homelessness. Before Dada, “grinding poverty” drove her into sex work to feed herself. Among the literally starving artists in Europe circa World War I, Dada’s mama had to eat. Then, as artillery shells fell in the distance, she started the greatest cabaret in the history of the world.

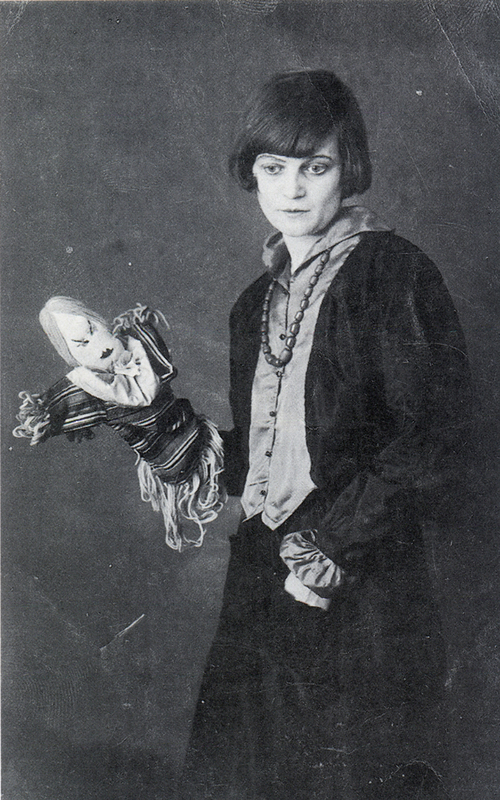

Hennings circa 1910-1913

The Founding Act of Dadaism

Hennings and boyfriend Hugo Ball fled Germany to Switzerland, starting the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich. Often Ball is credited with starting it, or the couple are credited together because they co-owned it. But art historian Roselee Goldberg, in her 2016 lecture “Dada and Dance” at the Yale University Art Gallery, insists (@24:25-27:02) that Hennings, not Ball, was the prime mover behind the Voltaire. Noting Hennings was a lifelong cabaret artist with a fiery personality, whereas Ball was suicidally depressed and quiet, Goldberg says, “Nothing could convince me this was Hugo Ball’s idea all by himself … She’s come from cabaret, it’s what she’s most comfortable doing.”

Hennings was already an internationally-celebrated singer/cabaret star, an “erotic genius” dazzling audiences with song, dance, acting, readings, puppetry, and costumery. She was also a painter, and a widely-published poet and novelist. Ball was a writer too, and a pianist, a fellow visionary entertainer. The couple established Dada by anchoring their vibrant and vital cabaret, a nightlife art space where “anything goes.” The aim was a critique of civilization in the form of a primal scream, and they put out a call for like-minded artists. If only life could be art, instead of war … Zurich Dadaist Hans Arp described a typical scene from the Cabaret Voltaire in his essay “Dadaland,” written 32 years later, in 1948. He had just witnessed his second World War:

“On the stage of a gaudy, motley, overcrowded tavern [we] are several weird and peculiar figures … Total pandemonium. The people around us are shouting, laughing, and gesticulating. Our replies are sighs of love, volleys of hiccups, poems, moos, and the meowing of the medieval Bruitists [noise poets]. Tzara is wiggling his behind like the belly of an Oriental dancer. Janco is playing an invisible violin and bowing and scraping. Madame Hennings, with a Madonna face, is doing the splits. Huelsenbeck is banging away nonstop at the great drum, with Ball accompanying him on the piano, pale as a chalky ghost … Despite the war it was a lovely era which we will always remember as idyllic when the next world war comes and we are changed into hamburgers.”

Zurich in 1916 bubbled with creative ferment, a cross-pollination of international artist refugees. This was the energy Hennings tapped into. Her crowd-pleasing abilities made Dada a community-building exercise. Audiences freaked out to the unrestrained, rule-breaking performances and exhibitions; the Voltaire featured immersive multimedia before it was cool. Then, accompanied by Ball on piano, Hennings united the room in song — beloved folk songs, bawdy bordello songs, and savage political numbers.

Hennings and Sophie Taeuber — the other woman in Dada’s inner circle — were both painters, costumiers, dancers, and puppeteers who made their own puppets. Their complementary work did a lot of heavy lifting at the frenzied events. Did the Impressionists have dual puppeteers? Answer: No. Dada was something beyond. The Voltaire lasted less than six months — but more than a century later, we are still talking about it.

Hennings with Dada puppet, Zurich, 1916

Life After Dada

Zurich Dadaist Hans Richter observed infidelity and jealousy in Hennings’s and Ball’s relationship (Art and Anti-Art, 2016 edition, p. 70): “Naturally, there were occasional problems; for example Emmy Hennings could not decide whether to leave Ball for the good-looking, fiery Spaniard [Julio Alvarez] del Vajo. Ball followed them around with a revolver in his pocket (so Emmy said), and the two lovers hid in my flat, eluding their pursuer by a hair’s breadth. Since Emmy could not decide for herself, [Zurich Dadaist Tristan] Tzara and I met to discuss the problem and finally induced Emmy to go back to Hugo, her sorrowful knight. Soon afterwards they were married.”

Hennings and Ball married on February 21, 1920. They were mismatched personalities, and it is widely assumed Hennings played the field. But they were also dear soulmates who shared interests and beliefs. They had no children together, but Hennings’s daughter Annemarie came to live with them.

What started in the Voltaire moved through Zurich galleries before spreading across the world. Burned out, Hennings and Ball left Dada and toured hotels with a new troupe. Hennings took the stage name Dagny, one of her many name changes — a factor complicating complete attribution of her work.

The couple settled into a life of writing and a profound Catholic mysticism. When she wrote about their wild and un-Christian Dada past, she retroactively rationalized it into their faith. Scholar Renee Riese Hubert wrote in her essay “Zurich Dada and its Artist Couples” (Women in Dada: Essays on Sex, Gender, and Identity, 1998 edition, p. 524): “We understand the move from entertainment to love and mysticism as the dominant factor in Hennings’s life.”

Roselee Goldberg quotes one of Hennings’s autobiographical novels as saying, “My only profession is learning what I am.”

Hennings outlived Ball by two decades. She died in 1948 at a clinic in Sorengo, Switzerland. Her writing resides in an archive in Bern available to academics. Goldberg states there is a large body of Hennings’s work at Bern that is unknown to the public.

Scholar-poet-artist Crystal J. Hoffman summed up Hennings’s complexities and contradictions in her paper “Emmy Hennings: ‘Star of the Cabaret Voltaire’ and Dada’s Mystic Mother”:

“Her contradictory existence could never be made sense of. She was largely considered unintellectual; however, she was a well-published writer and an active member of the Bohemian intelligentsia. She was against systems and an anarchist; however, she longed for the comfort of Catholicism and would have been a nun had her nature allowed for it. She was fiercely independent and unrooted; however, she longed for the companionship of men, even when it did more harm emotionally and spiritually than it did good. She had more life experience packed into her short years than most of her companions could boast of, as a prostitute, drug user, shyster, vagabond, mother, and wife; however, she gave the impression of naiveté, simplicity, and of having a child-like nature. It was for these paradoxes that she was almost entirely erased from the history of the movement that she helped to found and largely inspired. It was for these paradoxes that she felt the need to spend the latter part of her life writing and rewriting her history and that of her savior and spiritual other half, Hugo Ball … [D]espite Hennings’s own rewritings she [should] be cast in her proper role in the mythos of Cabaret Voltaire, simultaneously its Mystic Mother and High Priest.”

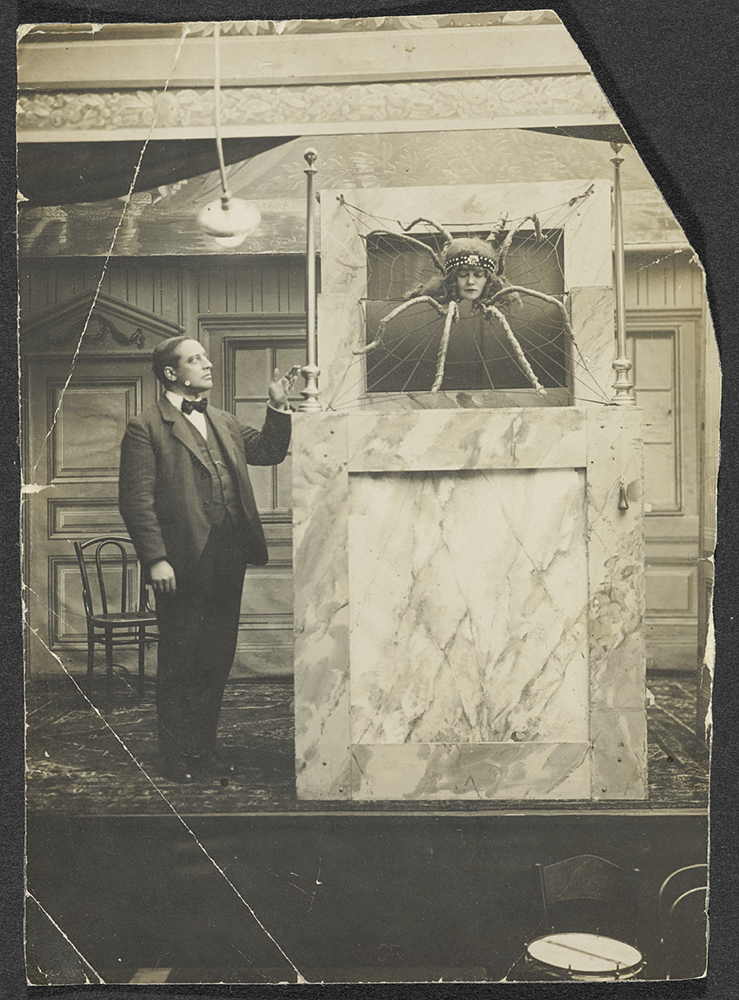

Hennings as Arachne, 1915

But Did Her Heart Belong to Dada?

In “Zurich Dada and its Artist Couples”, Renee Riese Hubert writes (pp. 519-520): “In spite of her indispensable role, her vitality, and her spontaneity, we may wonder to what extent Hennings’s heart really belonged to Dada. Do the singing and reciting of texts, many of them having little to do with Dada, count so heavily that we can dismiss her lack of an ideological involvement? To what extent did her Dada performances really differ from her cabaret roles? … Most of her poetry, so critics claim, belongs to the expressionistic vein: emotional, subjective, somewhat linear in its narration.”

Hubert is basically wondering if Hennings was weird enough or nihilistic enough to be a real Dadaist. First note that “the singing and reciting of texts” is an incredibly reductive characterization of Hennings’s contribution. Secondly, note the grateful quote from Zurich Dadaist Richard Huelsenbeck: “If it hadn’t been for her songs, we would have starved to death.” Thirdly, the poet and translator William Seaton reconciles Hennings and Dada in his book Dada Poetry: an Introduction (2013 edition). Seaton’s question is not “to what extent Hennings’s heart really belonged to Dada”, but to what extent Dada belonged to Hennings. He views Hennings and Dada as inextricable (pp. 47-48):

“(Her) poetry is richly suffused with a tone that goes far to explain the origins of dada. She establishes a mood that was to persist in German art, particularly theater and painting, for decades. In her poems a malaise, a conviction of some intolerable derangement in things is linked with a nearly desperate eroticism, yet expressed with redemptive poise and precision … As a performer she engaged in dada acts of provocation … She was called ‘the shining star of the Voltaire’ in the Zuricher Post and Ball always said she was a fully responsible collaborator … She took risks, agitating for revolution and forging documents for draft dodgers (for which she received a brief prison sentence) … Her work expresses the malaise of the era and the Bohemian reaction, heavy with dread yet scintillating with spirit and extravagance … expressing the horror and … ‘belatedness’ of the twentieth century. Many of her lyrics seem in a way the counterpoint to [Berlin Dadaist] George Grosz’s scenes of bestial carnality among the ruling class. With the world disintegrating, she, too grasps after some version of love.”

Seaton interprets Hennings’s work not as a “lack of ideological involvement,” but as one end of a spectrum — a “counterpoint” providing tension with her mostly male colleagues. Hennings, living her revolutionary life, staked out her own artistic territory within Dada. The red herring of her “ideological purity” — whatever that is — minimizes her foundational, central contribution.

Hans Richter saw it much the same way. In his view, the Dadaists were so different from each other that it makes no sense to single out anyone; their differences made them stronger as a group. In Dada: Art and Anti-Art, he wrote (pp. 12-27):

“(T)he magic fusion of personalities and ideas took place which is essential to the formation of a movement … It was [in Zurich], in the peaceful dead-centre of the war, that a number of very different personalities formed a ‘constellation’ which later became a ‘movement.’ Only in this highly concentrated atmosphere could such totally different people join in a common activity. It seemed that the very incompatibility of character, origins and attitudes which existed among the Dadaists created the tension which gave, to this fortuitous conjunction of people from all points of the compass, its unified dynamic force. The real, unmythologized history of Dada is the sum of the achievements of all these individual particles of energy. This is the key to that ‘unification of opposites’ which became an artistic reality, for the first time in history, in the shape of Dada … The Cabaret Voltaire was a six-piece band [Richter includes Hennings but excludes Taueber in this count] … miraculously, they found in the end that they belonged together and needed each other. I still cannot quite understand how one movement could unite within itself such heterogeneous elements. But in the Cabaret Voltaire these individuals shone like the colors of the rainbow, as if they had been produced by the same process of refraction.”

To Richter, the variety of Dadaists was a democratic feature, not a bug. No one in the audience at the Voltaire questioned Hennings’s bona fides.

Academics quibble about Hennings’s ideological involvement, but it seems just another way to “otherize” the only woman near-universally acknowledged as part of Dada’s inner circle. I say “near-universally” because even modern feminist Dada scholars can overlook her.

Irene Gammel provides a good example of this, in her book about the flamboyant Baroness Elsa, the Dada queen of New York City (Baroness Elsa: Gender, Dada, and Everyday Modernity, 2002 edition). In this otherwise authoriative book, Gammel inexplicably lists Dada’s founders as “the Roumanian Tristan Tzara, the Alsatian Hans Arp, and three Germans — Hugo Ball, Richard Huelsenbeck, and Hans Richter” (p. 10). The exclusion of Taueber is common enough. But omitting Hennings is egregious. It’s almost like she doesn’t want Hennings to complicate her portrait of Baroness Elsa. Hennings and the Baroness indeed shared striking similarities: both were dancer-performer-artist-writers born in small seaside towns, who participated in the Munich and Berlin avant-garde before leaving Germany, and did some hard living.

The Baroness joined Dadaism in New York after Hennings birthed it in Zurich. The weird, anarchic Baroness has become feted as a more “ideologically pure” female Dadaist, eclipsing Hennings’s star. The Baroness has even been called “Dada’s mother” — as has writer Gertrude Stein, who was even further removed from Dada’s origins. But neither of those women started the greatest cabaret in the history of the world as World War I thundered in the distance. Among all who have a claim to the title, Hennings is Dada’s one true birth mother.

Hennings circa 1912-1913

“Ignoring Her Contributions is Unforgivable”

In her 2007 paper “Sex and the Cabaret: Dada’s Dancers,” scholar Ruth Hemus addresses how Hennings succeeded artistically despite her traditional cabaret role of sexualized eye-candy:

“Women performers were generally offered up as an attractive visual spectacle to cabaret goers, and to some extent this was continued within the avant-garde. The Dada singer, diseuse and poet Emmy Hennings was undoubtedly a selling-point for the Cabaret Voltaire. She is recalled as frequently in Dadaists’ memoirs for her sexual presence on and off stage, as for her spoken and written voice. Tzara described the cabaret as ‘the cosmopolitan mixture of god and brothel.’ If Ball’s sound poetry produced uncanny religious and spiritual moments in the cabaret, Hennings’s physical and sexual appeal evoked a highly-charged sexual atmosphere in a cabaret filled mainly with men. As Huelsenbeck recalls: ‘There were few women in the cabaret. It was too wild, too smoky, too way out.’ The more radical aspects of Hennings’s contributions are easily obscured — her choice of song; her repertoire of poetry; her deliberate shrillness — but arguably, they were all the more effective because of the audience’s expectations of women performers to be looked at and enjoyed.”

Relatedly, I detect a sexist sneer in the often-quoted, otherwise positive Zuricher Post review of a Dada evening. The critic cannot help but comment disapprovingly about Hennings’s body: “The star of the cabaret, however, is Mrs. Emmy Hennings. Star of many nights of cabarets and poems. Years ago she stood by the rustling yellow curtain of a Berlin cabaret, hands on hips, as exuberant as a flowering shrub; today too she presents the same bold front and performs the same songs with a body that has since then been only slightly ravaged by grief.” (A slightly more sympathetic translation reads: “The star of the cabaret however, is Mrs. Emmy Hennings. The star of who knows how many nights and poems. Just as she stood before the billowing yellow curtain of a Berlin cabaret, her arms rounded up over her hips, rich like a blooming bush, so today she is lending her body with an ever-brave front to the same songs, that body of hers which has since been ravaged but little by pain.”)

Crystal J. Hoffman addresses “the unfortunately extraordinarily gray area of [Hennings’s] period of involvement with Zurich Dada,” finding that Hennings underplayed her own role: “Hennings preferred to keep from history most of the creative work produced during her long career as a member of Munich and Zurich’s Avant-Garde inner circles, as it would unfortunately also reveal a long career as a morphine addict, prostitute, and hustler, who frequently promoted free-love, anarchy, and social revolution, and spent several stints in prison, at least once for forging passports for draft dodgers. For this reason, it seems that Emmy Hennings welcomed individual artistic anonymity in favor of becoming a footnote to Hugo Ball’s career.”

But this is not an excuse for modern academics to underplay Hennings’s role. Hoffman faults “renowned DADA scholar(s)” — among others, Richard Sheppard in his 2000 book Modernism-Dada-Post Modernism. Hoffman writes:

“(D)espite the recent resurgence of interest in the female Dadas and new sources of information on Hennings’s early life, with the publication of formerly unavailable journals of her peers … Sheppard fails to [fully] note Hennings’s contribution … I struggle to see any reasonable cause for this glaring oversight … [He] inexplicably gives Hennings neither agency nor voice … Earlier histories of Dada … often mentioned Hennings as a side-note, despite the fact that she was called the ‘Star of the Cabaret Voltaire’ by the Zurich Chronicle, had paintings hanging in the Galerie Dada alongside Kandinsky and Arp, and was largely responsible for founding the Cabaret Voltaire. In fact, you can rarely find her name in their indexes. However, ignoring her contributions at this point is unforgivable.”

“Portrait of Emmy Hennings,” etching circa 1913 by Reinhold Rudolf Junghanns

Hennings and Ball: “In Art and In Life”

In the absence of English translations of her autobiographical books, some of the best information about Hennings is in Ball’s autobiography, Flight Out of Time: A Dada Diary (1974 edition). I bought the book to find information about her and it did not disappoint. Although the reader has to wade through Ball’s ponderous musings on philosophy and theology, one also comes away with an intimate picture of Hennings. Ball’s account of their marriage is unfailingly tender. The couple read plays, books, and letters aloud to each other, went to church together, and dreamed of each other.

When Hennings’s nine-year-old daughter Annemarie came to live with them, following the death of Hennings’s mother who had been raising her, Ball wrote (p. 65): “Annemarie was allowed to come with us to the [Dada] soiree. She went wild over all the colors and the frenzy. She wanted to get up on stage and ‘perform something too.’ We had a hard time holding her back … We welcomed the child, in art and in life.”

Hennings’s physical health appears fragile at times (p. 96): “Emmy fainted in the street. We were waiting under a streetlamp for the tram. She leaned against the wall, staggered, and gently collapsed. I got help from passers-by, and we carried her to the first-aid post in the nearby police station. Her little head was resting so peacefully and comfortably on my shoulder as I was carrying her. A strange scene in the police station: the two of us on and by the bed, and six or seven worried policemen’s faces around us, giving her some water and stroking her blond hair. On the way home she smiled and said, ‘Why is your mouth so bitter?’”

Another anecdote about her health (p. 159): “My book Zur Kritik der deutschen Intelligence has been published … I gave Emmy the first copy for her birthday and took it to her in the hospital where she was suffering from a severe case of pneumonia. She had a high fever, barely recognized me, but caressed the book I brought her and smiled in a sad way as if she were saying goodbye forever.”

Ball’s diary is an invaluable source for Hennings’s writing; he records several poems in whole or in part which otherwise may have been lost or untranslated, as in this passage (p. 160-161):

With Emmy, tired and drained, on the deck chair. It is nice to fall asleep slowly while she attends to her little jobs. She puts a lighted cigarette in my mouth; gives me an ashtray, and taps the ash into it herself. There is a cold draft through the crack in the door, so she covers me with her brown coat and makes pancakes. That is very nice … Emmy has given me a poem:

We are still holding hands.

Time shines brightly in long rows.

Look, white lilies will soon snow down,

The hearts will be wasted.Now you are I, and I am you,

The street is a white dream.

We keep playing at wandering,

Changing places in the far distance.And one day there will be a white snow flurry.

Then I will flee to your countenance.

Dreaming of you – O gentle drowning! —

The brightest light plays around us.

The couple got to know the writer Herman Hesse, who called Hennings “a fairy-tale bird and a little angel” (p. 206): “It is evening, and we are sitting in the grotto [talking with Herman Hesse], under a tall beech tree. The tree sheds two withered leaves. Emmy and Hesse reach for them.”

As mentioned by Thomas Rugh in his paper “Emmy Hennings and the Emergence of Zurich Dada,” she had been born in the coastal city of Flensburg and “considered herself a seaman’s child.” Rugh translates a passage from one of her books, Ruf und Echo: Mein Leben mit Hugo Ball (“Call and Response: My Life with Hugo Ball”): “Because I am a seaman’s child, stem from the sea, life itself is to me a journey over the sea, and I never see the shores, as if the land, which I don’t know yet and which awaits me, were sleeping in peace. It might be my homeland or a strange land that I will love, I don’t know. Always it was the adventure which I did not seek and which befell me.” Related to that, Ball writes (p. 207-208): “With Emmy for the May Day services in Loreto … Then on the way home we bought a fish at Bernadone’s, and when we got home we put it in water. Emmy really is the lady of the sea. Fish are the only animals she can touch and take in her arms.”

Hennings in 1930

Hennings the Writer

Ball admired and praised her writing, proudly recording press about it. Many times he enjoyed her linguistic skills and creative insight, as in the following examples:

Page 80: “Wonderful day. It is quite something to have experienced it … Emmy thinks the German language is poor in words of tenderness and grace. Danish is infinitely richer. A conversation about grace, at five o’clock in the morning. It is that thousandfold discovery of little decorative and enriching tendernesses.”

Page 167: “People are beginning to be interested in Emmy’s Gefängnis [“Prison”]. The book expresses the character of the age and its sufferings. A Berlin critic calls it ‘modern memoirs from a charnel house’ … A Munich journal writes: ‘One-third child, one-third woman, one-third gamin [street urchin], the author of this book stands out from the many similar to her because the archetypal human element in her sympathetic, gentle hands glows like a red ruby, compared to which everything else disintegrates into gray ash.’ The book is stylistically an incessant filing and gnawing at iron bars. It knows no capitulation, no compromise. It is unshakeable in its precise honesty.”

Page 196: “Emmy’s Das Brandmal [“The Branding”] has come out. There is no debate here. Here is this age, experienced and suffered physically. It is always significant that it is the poets who replace philosophers and theologians. One just cannot perceive the outrageous things in one’s vicinity without carrying them in oneself.”

Page 202-203: “From Emmy’s new poems:

I sing of infinity!

O time, are you so snowbound?

Sung so white, rose-red!

The fruit of love, blood of death!

Hear my song of conspiracy to the night!

Deep in the day, ablaze in the bright night! With you awake, weeping, smiling”

Page 205: “Die Frankfurter Zeitung hails Emmy as a German poetess as follows: ‘E.H., a nomad of many one-night stands all over the fatherland, has finally and indisputably found a home in the realm of poetry with her Brandmal. There is a flagellant’s search for truth in this book … Awe and ecstasy of vision harmonize throughout with minute observation … Somnambulistic and happily disembodied in the gloom of the great Catholic cathedrals … The solidarity of H. with these creatures is perfect. Since she revels in humility, it would be an honor for her to be titled Prima inter Pariahs [First among Pariahs].’”

Hennings in Agnuzzo, Switzerland, circa 1930

Finding Her Religion

Hennings was a magical thinker with a deep sense of mysticism. Flight Out of Time contains several examples of the couple’s piety and their perception of signs and portents.

Hennings appears to have believed (she may be forgiven for this) that World War I was literally hell manifesting on Earth (p. 81): “‘The people involved in the battle of the Somme,’ says Emmy, ‘cannot have any inner conflicts. It is planned that way.’ She regards the battle of the Somme as the real hell that was prophesied. She saw a picture of people with animal-like gas masks that resembled trunks and snouts. ‘Since then I have been quite convinced that it is really hell that is being written about. Why should that not be possible?’”

Page 163: “I usually spend the evenings now with Emmy in her Marzilli room [the couple maintained separate bedrooms when they could]. She tells stories or reads to me from the biography of Saint Francis by Thomas of Celano, from Thomas a Kempis, or from Anna Katharina. She takes so much trouble for me. I have borrowed the Bittere Leiden unseres Herrn [Bitter Suffering of Our Lord] from her and have dipped into it.”

Page 163: “[We are looking at] a cabalistic sketchbook with demonological images. Devils displaying an intentional banality to hoodwink people about the fact that they are devils. Plump, chubby-cheeked peasant girls, who end up in a lizard’s body. Monstrosities born of the fiery regions, fat and importunate. ‘I’ve seen him!’ Emmy cries, and points to a squint-eyed fellow with pendulous breasts and pig’s feet.”

Page 200: “Today Emmy read me the beginning of a new book. It starts as follows: ‘Praised be all names that harbor life. Praised be all naming that aims at the birth of the unnamable. Let fulfillment live in every word that longs for wordlessness.’ We go into a Canvetto. As we turn the corner into a little nook of the wood where there is the figure of the stigmatized Francis with the crown of brambles, an unimaginably large white bird flies up. Someone says it was a wild duck; another says it was a heron, a sea eagle, and so on. Annemarie says quite calmly and softly: ‘It was the Holy Ghost.’”

The family in 1925

“After the Cabaret” by Emmy Hennings (translated by William Seaton)

I see the early morning sun.

At five a.m. I homeward stroll,

The lights still burn in my hotel.

The cabaret is finally done.

In shadows children hunker down.

The farmers bring their goods to town.

You go to church, silent and old

grave sound of church-bells in the air,

and then a girl with untamed hair

wanders up all blear and cold:

“Love me, free of every sin.

Look, I’ve kept watch many nights.”

Other essays in my Avant Garde Women series:

–Eliane Brau: The Invisible Icon

–The Shakespearean Tragedy of Peggy and Pegeen Guggenheim

–Michele Bernstein: Queen of the Situationists

–Sophie Taeuber, Founding Dadaist

–The Hundred-Jointed Dancer and the Laban Ladies

–Review of the Novel “Branded” by Founding Dadaist Emmy Hennings

An index of all Jim Richardson’s essays may be found here.

Recommended Links:

Leave a Comment

Only registered members can post a comment , Login / Register Here

2 Comments

Sweetgrass11

about 2 years agoJim Richardson (aka Lake Superior Aquaman)

about 2 years ago