Avant-Garde Women: Sophie Taeuber, Founding Dadaist

The multitalented Swiss artist Sophie Taeuber was one of the original Dadaists in 1916. Working in many media at the cutting edge of modern art, she went on to Surrealism and more. She remained lesser-known for sexist reasons even while many art historians considered her a crucial and pioneering figure. Her work was overshadowed by male contemporaries, and even though art history tended to minimize her, if anything the situation has all but reversed itself now: her star has brightened while others have dimmed. Decades after her death in 1943, Taeuber continues to emerge from the shadows of the avant-garde.

The multitalented Swiss artist Sophie Taeuber was one of the original Dadaists in 1916. Working in many media at the cutting edge of modern art, she went on to Surrealism and more. She remained lesser-known for sexist reasons even while many art historians considered her a crucial and pioneering figure. Her work was overshadowed by male contemporaries, and even though art history tended to minimize her, if anything the situation has all but reversed itself now: her star has brightened while others have dimmed. Decades after her death in 1943, Taeuber continues to emerge from the shadows of the avant-garde.

A note on spellings etc.

Different sources below refer to Dada either as “dada,” “Dada,” “DADA,” “Zurich Dada,” or “Zurich-dada.” All are synonymous for our purposes. The Zurich branch of Dadaism that Sophie Taeuber helped create in 1916 was the founding branch of the movement, propagating to other cities after she moved on. Indifference to standardized capitalization was a Dada hallmark.

Sophie Taeuber is referred to by different sources as either Taeuber or Taeuber-Arp. She had made a name for herself before she married Jean (Hans) Arp in 1922, which is why I think she hyphenated instead of taking his name. Whereas it’s most correct to use “Taeuber-Arp,” the legal name she died with, some folks just use “Taeuber.” One source I found switched between Taeuber and Taeuber-Arp in the same document, so I don’t think it really matters. I’ve opted to just say Taeuber (pronounced “toy-burr”).

“Founding Members” vs. “Participating Girlfriends”

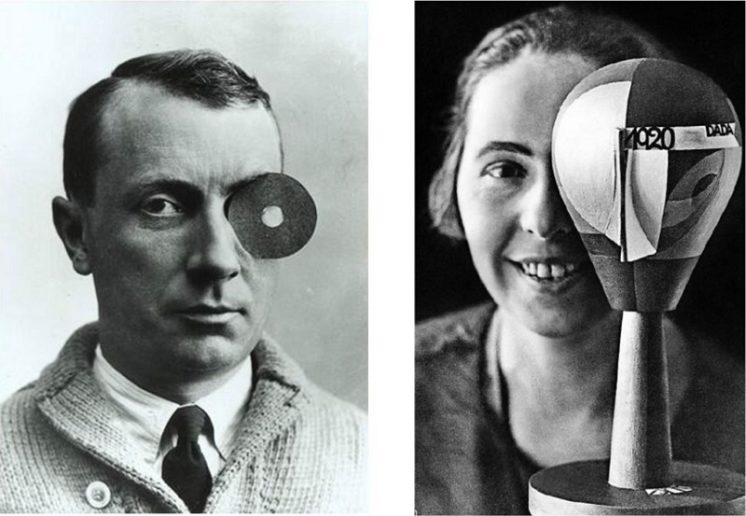

Consider the 1927 autobiography of Taeuber’s fellow founding Dadaist Hugo Ball, Flight Out of Time. The 1974 edition has an introduction by art historian John Elderfield which contains these lines: “Who exactly constituted Zurich dada is not so anomalous a question… Besides the five principal founding members (Ball, Arp, Janco, Tzara, Huelsenbeck), we recognize participating girlfriends (Emmy Hennings and Sophie Taeuber).”

From that we see how the question of the Dadaist women’s “membership” was being framed as late as 1974: the women were being recognized, but as “participating girlfriends” instead of “principal founding members.”

This girlfriend-or-founding member dichotomy came up in my profiles of Eliane Brau and Michelle Bernstein, both of the Letterist-Situationist scene in 1950s-60s Paris.

Michelle Bernstein is considered a “founder” of the Situationists instead of a “participating girlfriend” (although she was that too) because she wrote and co-wrote crucial Situationist documents. (Even considered a founder, her role remained overlooked.)

Eliane Brau on the other hand is considered a “participating girlfriend” instead of a “founding Letterist,” even though she exemplified Letterism from its first moments. But the one thing she wasn’t doing in those early days was writing. She didn’t leave enough traces in the record for historians to define her properly. From what I can tell, writing manifestos and so forth is the ticket to the boys’ club, and that gets you called a founder.

Eliane Brau’s case is similar to Taeuber’s before her, because they each co-signed the founding manifestos of their respective groups, and were highly involved in all foundational activities, but each woman wound up being defined as a “participating girlfriend.” Because merely co-signing manifestos is not enough, you have to write them. Or historians might call you girlfriends instead of artists.

A New York Times article on Taeuber documented her feelings about all the manifesto-writing going on, in a 1919 letter to her husband “when the Dada movement was at a fever pitch, with its devotees penning manifestoes left and right.” Taeuber wrote, “I’m furious. What is this nonsense, ‘radical artist.’ … It must only be the work, to manifest oneself this way is more than stupid … Nobody cares if you’re always hopping around on your vanity like this.”

In Taeuber’s case, it took until the 1980s but she shed the “girlfriend” label somewhat, and is now treated on more of an equal footing with her male counterparts. In many cases she exceeds them. Consider that the male Dadaists effectively got decades of a head start on her in terms of exposure and academic attention. Taeuber also made less art than say, her artist husband. But in contrast to him, she was both working and being domestic. And she also helped him with his art.

Maybe it’s like they say about Ginger Rogers: she was actually a better dancer than Gene Kelly, because not only could she dance as well as him, but she did it backward in heels.

So about Taeuber’s role in Dada, we should count seven founding members instead of five. The participating girlfriends need to be promoted to founding members, full stop. We can trace the progress of the issue in the literature. Consider how Naima Prevots framed it in a 1985 issue of Dance Research Journal. (This was eleven years after 1974’s phrase “participating girlfriends” was used by John Elderfield.) Prevots put it like this: “The Zurich Dada aesthetic was formulated primarily by the activities of seven individuals … Jean (Hans) Arp, Hugo Ball, Emmy Hennings, Richard Huelsenbeck, Marcel Janco, and Sophie Taeuber.” See how Prevots removed the artificial gender divide between “participating girlfriend” and “founder.” Now all seven artists were being written about as equals. Prevot’s phrasing eliminates the segregation of the boys’ club manifesto system, asking more democratically, “Who formulated the aesthetic?” Articulated thusly, Dada has seven founders instead of five. Miraculous!

One way to look at it is how Carolyn Lanchner put it in 1981, for the MoMA exhibition that marked a turning point for Taeuber’s recognition in the art world: “Early phases of (Taeuber’s) career took place in Zurich between 1915 and 1920 at the very center of Dada activity in that city.” This wording avoids the dichotomy of founder/girlfriend, and even of “who formulated the Dada aesthetic.” Instead, Lanchner merely points out that Taeuber and Dada are inextricable in space and time. They always have been. Which is why, even if you don’t consider her a real Dadaist, the onus is on you to address her existence. She was there. Dada wouldn’t have been the same without her.

Unfortunately, I have also found some backsliding in the critical community. Like in the paper by Tanja Malycheva and Isabel Wünsche in 2017 where they claimed Dada had six founders: “The only woman in the Dada circle was Emmy Hennings … While Taueber joined the Dadaists on many occasions, she was also the only one who had a daytime job and regular income … She was head of the textile department at the Zurich Arts and Crafts School.”

Malycheva and Wünsche are arguing that Taeuber merely “joined the Dadaists on many occasions,” i.e., the “participating girlfriend” hypothesis, combined with having a job somehow counting against her. She was the only Dadaist with a real job. “The only woman was Emmy Hennings” my ass. Do they deny Taeuber a role in formulating the Dada aesthetic? It’s irrefutable. Do they deny that early Dada and early Taeuber are as inseparable as quantum phenomena?

Taeuber was also the star dancer of the Laban dance school, whose “Laban ladies” had a larger impact on Dada than previously acknowledged.

Renaissance Woman

Taeuber is noted for her trailblazing creativity and formal mastery in many different media, including visual arts, textile arts, woodworking, and dance. A survey of several sources shows her extreme versatility. Wikipedia documents that she is an “artist, painter, sculptor, textile designer, furniture and interior designer, architect, and … dancer, choreographer, and puppeteer, and she designed puppets, costumes and sets for performances at the Cabaret Voltaire [where Dada was centered] as well as for other Swiss and French theatres … co-authored a book.”

According to this 1968 Dada documentary above (@6:20), Taeuber “as a painter had great influence on the Zurich-Dadaism. Paper- and clothpictures, embroidery, DADA-heads, marionettes. Dancer. Taught [actually she was a Professor of Textile Design, and the head of the Textile Department, at the Zurich Arts and Crafts School, what is now the Zurich University of the Arts].”

Art movements and styles she is associated with include Dadaism, Surrealism, Constructivism, and abstract art, particularly geometric abstraction. Taeuber is mentioned in the same breath as Mondrian; it has been said that if Mondrian is the artist of the right angle, Taeuber is the artist of the circle.

According to this lecture above by Walburga Krupp, “her reliefs were appreciated by Duchamp.” The New York Times wrote: “Among her advances was using interior design as an artistic tool, an early version of installation art, and when she wasn’t painting she made textiles, costumes and sculptures and edited magazines [including a Constructivist review]. She was a dancer, too … Taeuber-Arp was a multidisciplinary artist when it was radical to be so.”

According to the online Taeuber exhibition: “[She was a] pioneer of geometric abstraction … Mediating between different manifestations of modernism, Taeuber-Arp was … part of the connective tissue of the European avant garde … She spent 10 years as a student in several of the most pioneering schools of the day, including Wilhelm von Debschitz’s painting and interior design workshop in Munich and Rudolf von Laban’s dance school in Zürich.”

Fellow founding Dadaist Emmy Hennings had this to say about Tauber-Arp’s interior design: “The walls, covered with paintings, give the illusion of almost endlessly vast rooms. Here, painting makes the visitor dream, it awakens the depths in us … The house may become a treasure box, a reliquary, and one can always look at it with new eyes.”

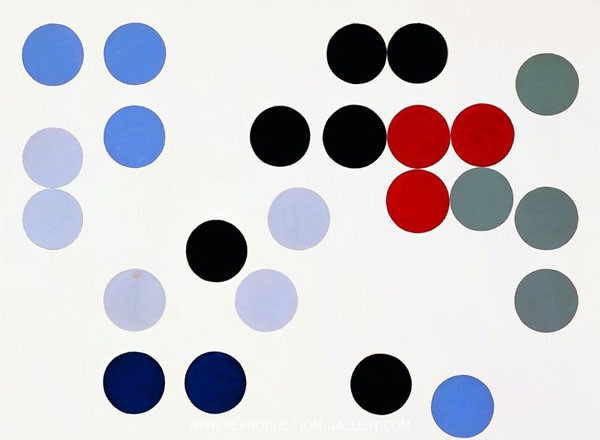

The book Sophie Taeuber-Arp by Carolyn Lanchner credits Taeuber with being the first to use polka dots in fine art. See Dynamic Circles, 1934. Hold up – Taeuber invented polka dots? It’s odd to think something like polka dots had to be invented. The same holds true for the Dada invention of collage. It’s something I learned how to do in kindergarten. But in 1916, things like collage, and polka dots, represented a new force in art: abstraction. Sort of all of a sudden, painting no longer had to be a picture of anything. New rules for art and design were free to be re-invented.

Artistic Polymath Power Couple

The poet-turned-artist Jean (Hans) Arp wrote, “The exhibition that was held at the Galerie Tanner in Zurich, in November 1915, was to be the greatest event of my life. It was where I met Sophie Taeuber for the first time.”

By the 1940s, the couple would become giants in the art world, seemingly knowing everyone. Their relationship saw extensive collaboration with each other, and they had similar artistic visions. Arp wrote about their joint efforts: “We wanted our works to simplify and transmute the world and make it beautiful” (“And So the Circle Closed,” in Arp on Arp, p. 245). Lanchner summed it up in 1981 for the MoMA (also including a quote from Taeuber’s fellow Dadaist Hans Richter):

“The period of Zurich Dada was for Taeuber a time of extraordinary activity, and, we may assume, of youthful happiness and fulfillment. She had met Arp, her one great love and the companion of her life; she was finding herself as an artist; she was totally involved in the exciting and stimulating circle of the Cabaret Voltaire, where she often performed as a dancer; and her appointment as Professor at the School of Applied Arts gave her and Arp the means to support themselves. Hans Richter, a close friend, recalls: ‘During the Dada period she had a job teaching at the school of arts and crafts, as well as being a painter and a dancer. In all three capacities she was closely associated with Arp. The first things of hers I saw were embroideries by Arp and later of her own designs. There were abstract drawings, extraordinary Dada heads of painted wood and tapestries, all of which could hold their own alongside the work of her male colleagues. She was Arp’s discovery, just as he was hers, and in their unassuming way they played a part in every Dada event.’”

Here’s a paper by Wünsche that quotes a contemporary of the couple, one Claire Goll, who saw their studio. Goll described the scene: “At most anytime you would find them busy with gluing, stitching, cutting, weaving or building marionettes, which they would let dangle from hooks in the ceiling. The mood was like the first day of Creation, Arp and Sophie re-inventing the world, together with new laws and possibilities of understanding. There was nothing ethereal about this couple; they resembled two winged ants or butterflies above a flowering meadow; she gracious, smiling, calm; he amused and comical.”

The Wünsche paper, which is about several women artists, describes the domestic household of Taeuber and Arp:

“Among the women artists discussed here, Taeuber seems to have been the most self-assured and versatile, able to bridge the responsibilities of everyday life and her artistic work. ‘She did not distinguish between washing dishes and writing poetry, embroidery and shining shoes. Every activity merited the same regard and commitment. This utter adaption to the moment made it possible for her to pursue her office as teacher at the arts and crafts school. She had not the slightest difficulty in reconciling the role of housewife with that of an avant-garde artist.’ The relationship between Taeuber and Arp, however, which appeared so eminently suitable and productive to their friends, put Taeuber into a position … (of providing) the main financial support for Arp; she organized the massive collection of objects and materials they amassed, brought home from the school colored papers and other artistic materials, and let him use the tools available at the school. She even executed a good number of his works. In an exhibition at the Kunstsalon Wolfsberg in Zurich in November 1916, eleven textile works by Arp had shown, eight of which had been executed by Taeuber [another time, some of Arp’s paintings had been shipped to an exhibition with wet paint and had gotten ruined, and Taeuber was the only one who could redo them]. ‘Her main achievement lay in her intuitive understanding of Arp and her translation of his ideas into something doable … If he was curious as to how an effect would be perceived in another medium, she would grab her sewing kit and thimble and cheerfully and meticulously embroider away until exactly the desired effect had been achieved.’”

It seems to me Wünsche has maintained a persistent bias against Taeuber in the two papers of hers I have quoted. In the first she said Hennings was the only woman in Dada. In the second she said Taeuber’s “main achievement lay in her intuitive understanding of Arp.” I reject that.

The Krupp lecture stated that essentially all domestic duties fell to Taeuber as a woman, and that her acquiescence was “conservative for avant-garde couples but common at the time.” The fairly standard example I remember was about entertaining at their household, with Taeuber in the kitchen while Arp held court in the living room etc. etc.

The New York Times article said Taeuber’s teaching job “kept the couple afloat.” 40 years later, Michelle Bernstein would be keeping Guy Debord afloat while in his shadow; the same dynamic appears at play between Taeuber and Arp. Her income helped his art, which overshadowed her own. Her output was less because she was working, and being domestic, and working on art.

In a 1937 letter, Taeuber wrote to a friend and complained about the art world: “As a woman it is ten times harder to hold your position in this caldron.”

It is generally acknowledged that she was and is overshadowed by her husband. At the same time, he helped her career. In a letter to her sister, expressing her view that the art scene was very closed to women, Tauber said, “Without the help of Hans, I would be finished as a woman, in the madhouse.”

According to the Krupp lecture, the couple’s collaborations were closer than previously known until letters came to light. That fits with Arp’s description: “In 1915, Sophie Taeuber and I did our first works based on the simplest possible forms in painting, embroidery, and collage. These were probably the earliest manifestation of a new kind of art. These works are Realities in themselves, without meanings or cerebral intentions. We rejected everything having to do with copying and description to leave Simplicity and Spontaneity in complete liberty.”

That is probably what this is referring to: “The Dadaist Hans Arp … recalled that once in Zurich, he and Taeuber rejected all rules of the established avant-garde. The collaborative textiles and duo-collages of 1916–18 do resist categorization with Cubism or Futurism. Instead, the partners juxtaposed varying avant-garde strategies that would be mutually exclusive for other artists—and certainly for most art historians of modernism. In their work, we see what seems like arbitrary collage arranged on a logical grid; there are Readymade materials (metallic papers [possibly brought home by her from the Arts and Crafts School], modularly cut or roughly torn) that nonetheless express an image of sensual aesthetic texture and form.”

The couple operated, or could operate, as an art team. They each had their own stuff, but similar to each other’s. Their interests were so aligned they could finish each other’s works and so on. Their radical-at-the-time aesthetic plowed into Dadaism. There is at least one critic who thinks the other Dadaists weren’t up to the task:

In 1917, following the example set by Hans Arp and Sophie Taeuber, more and more Dadaists began to express themselves using nonfigurative forms … Considered today, with the notable exception of those of Hans Arp and Sophie Taeuber, the artworks produced by the Zürich Dadaists may seem somewhat disappointing. After his figurative period – which was, for that matter, fairly mediocre — Marcel Janco was never very convincing with his nonfigurative plaster reliefs and highly Expressionistic woodcuts. Hans Richter was influenced by Kandinsky, as his rather derivative Visionary Portrait shows. Otto van Rees did collages which, though they may have influenced Arp, are not themselves very successful … With their collages, paintings, watercolors, engravings, reliefs, and embroidery, Hans Arp and Sophie Taeuber – later to become husband and wife – produced the Zürich group’s major works.

So, let me wrap my head around the through-line of all these different sources. So far we’ve seen Dada’s founders may have been hacks, but Taeuber the “participating girlfriend” who “joined them on many occasions” “formulated their aesthetic” and “produced the group’s major works.” Do I have that right?

“Personnages”, 1926 cross-stich embroidery by Sophie Taeuber-Arp

Legacy

In 1943, Taeuber died at age 54 in a carbon-monoxide accident involving a malfunctioning gas stove. From the New York Times article: “Taeuber-Arp’s reputation was tended by Arp himself. ‘He did amazing work for her after she died by writing about her, publishing a catalog raisonné … He donated her work to European institutions, and he made sure she stayed in the public eye.’ Taeuber-Arp’s complicated legacy is exactly what appeals to contemporary artists like Sheila Hicks … ‘Her husband had a powerful personality, and it was a free ride into the inner circle,’ Ms. Hicks said. ‘She wouldn’t have had that without him … It was a challenge to live in those times and achieve her goals… I hope they don’t make her out to be a tragic figure … I love the agility of this person who was multitalented, and who was partnered with this super-popular guy … It was a win-win.’”

According to this paper, one reason Arp published a catalog of Taeuber’s work after she died is that it was not being done properly otherwise. He fought for her recognition as a serious artist, even as others tried defining some of her work out of art history:

Hugo Weber excluded all tapestry, fabrics, puppets and jewelry in his influential Catalogue Raisonné (1948). As a result, Taeuber’s art work was only catalogued in a limited way. Arp was furious about the improper reception of Taeuber’s art work and wrote: ‘The serenity of Sophie Taeuber’s oeuvre is inaccessible to those devoid of any soul and who live in confusion. Her works have sometimes been referred to as applied art. Both stupidity and wickedness are at the root of this appellation. Art can just as easily express itself in wool, paper, ivory, ceramics, or glass as in painting, stone, wood, or clay.’ … Hemus linked this problematic selection to the patriarchal structure of the Dada art scene (and of art history itself), as ‘some materials chosen by women (handicrafts for example) or art forms (dance) are considered less appropriate or trivial’.

This paper argues that “the formal variety of (Taeuber’s) work, some of which has been lost, has counted against her.”

This is all eerily reminiscent of how textiles and fiber artifacts have vanished from the fossil record, leading to the overemphasis on those “masculine” artifacts more likely to survive such as spear points and arrowheads. Fiber arts and technology, like clothing, rope, and nets for instance, do not appear among the stones and bones of prehistory.

Arp was a poet and penned poems to Taeuber after her death. They are in German and I have not found translations, except for a few lines including these: “A star takes shape according to your design…The light slips beneath your feet … the flower … vanishes, in its own light … It vanishes in its purity and gentleness.”

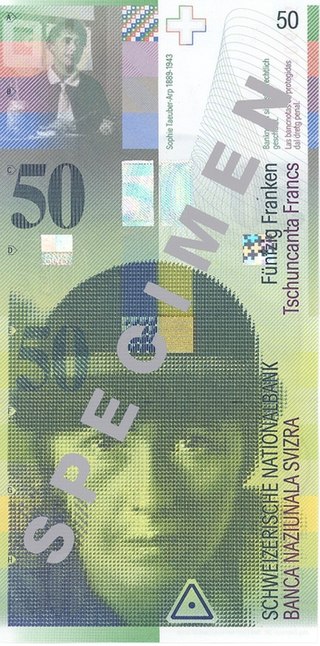

As Arp’s fame grew, he continued to promote Taeuber’s work, “giving it pride of place in his exhibitions.” Arp’s approach didn’t hurt: “Unusually among her female contemporaries, Taeuber-Arp’s fame grew rather than dissipated after her death.” In addition to growing numbers of major exhibitions internationally, “in Switzerland, she is perceived as a giant.” She is the only woman pictured on Swiss cash.

Also in my Avant-Garde Women series:

–Eliane Brau, the Invisible Icon

–The Shakespearean Tragedy of Peggy and Pegeen Guggenheim

–Michelle Bernstein, Queen of the Situationists

–The Hundred-Jointed Dancer and the Laban Ladies

–Emmy Hennings: “Shining Star of the Voltaire”

–Review of the Novel “Branded” by Founding Dadaist Emmy Hennings

An index of all Jim Richardson’s essays may be found here.

Recommended Links:

Leave a Comment

Only registered members can post a comment , Login / Register Here

No Comments