Duluth record labels boosted the scene, but are going extinct

Compact discs and cassettes of releases from Duluth record labels fill a plastic bin at the Perfect Duluth Day headquarters. (Photo by Paul Lundgren)

Mark Lindquist, the chief purveyor of local albums at the turn of the millennium, thinks he can succinctly describe the difference between the best-known Duluth record labels.

“Chair Kickers’ put out the most gorgeous records,” he said. “Spinout had the most professional. Chaperone had the coolest. And Shaky Ray had … the most.”

Shaky Ray Records was Lindquist’s enterprise. Though he modestly claims credit for the “most” album releases rather than using a word implying quality, his label was behind many of Duluth’s most iconic songs and put out the earliest works by some of the city’s most recognizable musicians — Charlie Parr, Dave Simonett, Jamie Ness, Crew Jones, the Black-eyed Snakes, the Keep Aways, and on and on.

Some of the Shaky Ray albums had printed labels and stylish sleeve art, but most were assembled at the dining room table with a do-it-yourself, punk-rock work ethic. Burn 50 compact discs, jam some black-and-white pieces of art into the jewel cases, scribble the title on the discs with a black marker and it’s good to go.

“You can probably see fingerprint marks,” Lindquist said of the discs he sold. “We stuffed those CDs ourselves. A lot of those are hand-stamped. Those seven-inch records, the album covers are off copy machines. It was pretty homemade.”

Lindquist figures the Shaky Ray discography totals something like 60 or 70 releases. Nearly all of the works have numbers cataloging them in something resembling chronological order, but the process was flubbed at some point.

“I’m pretty sure after, like, release 30, I just kind of lost track,” Lindquist said. “I think we would release, you know, fan ’zines sometimes with a Shaky Ray number. I wrote a one-act play and assigned it a Shaky Ray number. … I think I had parties and gave them Shaky Ray numbers.”

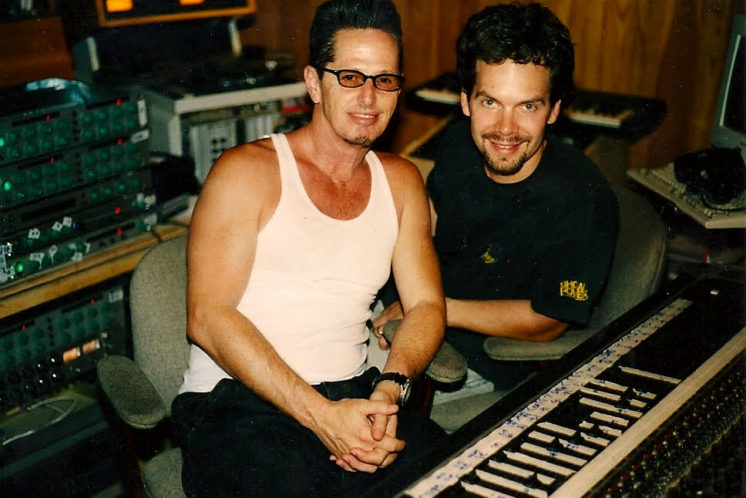

Bernie Larsen and Tom Fabjance at Inland Sea Studio in Superior during tracking of Gild’s 2001 release “Satellite Images.”

A DIY Scene

Medium and small cities are not supposed to have record labels pulling together the local talent. Yet Duluth has had several. Some were short lived, like Heat Street Tapeworks (circa 2014) and Automation Records Media Conglomerate (circa 2012). Lundeen Productions and ShowCase records released numerous compilation albums between 2004 and 2019, including 13 collections of Christmas music by Duluth-area artists and a series highlighting local music from the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s.

And, of course, common in any city are “vanity” labels — basically a cool sounding business name a band can put on its self-released projects. The distinction between vanity and legit can be blurry, but Duluth has had four labels in recent history that seem to stand out from the rest in terms of output by a variety of artists.

Trailing Shaky Ray in sheer quantity of music put to market are Chaperone Records and Chair Kickers’ Music, each with about 20 releases. Spinout Records exceeds them, but it’s not entirely a local label. Though it’s responsible for the highly regarded Duluth Does Dylan albums — a soon-to-be pentalogy of compact discs released from 2000 to 2021 featuring Duluth-area bands performing the works of Bob Dylan — a majority of Spinout music is not connected to the local music scene.

Spinout was launched in 1995 by Bernie Larsen, who had moved from California to Houghton, Mich., bringing with him years of experience recording music in his home studio.

Around the same time Larsen was launching Spinout, Tim Nelson was pioneering the craft brewing culture of Duluth, opening Fitger’s Brewhouse. Nelson began booking shows featuring acts Larsen was producing for Spinout from Houghton.

“Bernie created a scene back then in Houghton that really inspired what I was doing in Duluth,” Nelson said. “He had a little ’zine, he had a little club, he had a little a little studio, he had a label.”

Nelson followed Larsen’s lead, becoming a partner with his brother Brad in the Ripsaw newspaper and helping Scott Lunt develop the Homegrown Music Festival in Duluth.

“We did everything DIY,” Nelson said, noting that in Houghton or Duluth at the time there was “no one else to do it for you.”

At the end of 2000, Nelson and friends organized the original Duluth Does Dylan album and Nelson became a partner with Larsen in Spinout. There was also a time when Larsen moved to Duluth and lived with Nelson for about a year, making Spinout a fully Duluth label, briefly. Larsen has since returned to California.

In the past 25 years, Spinout has released at least 25 Duluth-related compact discs, including numerous works by Tim Nelson’s bands Gild, Boy Girl Boy Girl, Tryke, 500 Million Society and Timothy Martin, along with other artists like Jessica Myshack, Hattie Peterson and Shaunna Heckman.

Nelson said he’s not very involved in Spinout these days, but the friendship and music connection with Larsen remains. And the fifth Duluth Does Dylan album is in the works.

“It’s really about pumping the scene,” Nelson said of the ongoing project deploying the fame and works of the famous Duluth-born artist to raise the profile of modern Duluth bands.

In addition to the original, the series includes Duluth Does Dylan Revisited (2006), Another Side of Duluth Does Dylan (2011) and Bringing it All Back to Duluth Does Dylan (2016). The next in the collection is set for release in May 2022, and will include a track with Nelson and Larsen performing together.

Nelson said the first Duluth Does Dylan album is sold out, but he has some of the others in his closet.

“It’s a labor of love,” he said, noting that Duluth Does Dylan is a grant-funded nonprofit. “Never made any money on the thing. It just seems like we’ve got to keep doing it because it’s important in that it encapsulates the Duluth scene.”

Album art from Chair Kickers Music releases. Clockwise from top left: If Thousands’ “Yellowstone.” Haley Bonar’s “… The Size of Planets,” Rivulets’ “Debridement,” self-titled release by No Wait Wait and the Black-eyed Snakes’ “Seven Horses.”

How it Starts

The ubiquitous Alan Sparhawk has music spread out across each of the primary Duluth labels, and he operates one himself. That’s all supplemental to his main works with the band Low, which are on the Seattle-based label Sub Pop. On Spinout, Sparhawk has five songs with four different bands on the first four Duluth Does Dylan records; he appears on two Shaky Ray compilations as a solo artist; his band Retribution Gospel Choir released an album on Chaperone; and he’s released three blues/rock works with the Black-eyed Snakes on his Chair Kickers’ Music label, along with several Low specialty releases.

The Chair Kickers’ label began when Low decided to put out an EP of Christmas songs in 1999.

“In the late ’90s, everybody was, you know, DIY,” Sparhawk said, repeating the sentiments of Lindquist and Nelson. “The put-it-out-yourself kind of thing was right in there where we were at. It worked well, but it also had its limits. It was a time when the business was in a certain state, and of course that’s ever changing.”

Sparhawk planned a low-key release, with the notion that the six-track Christmas CD could be sold at performances and eventually make a small profit.

“It just seemed easy,” Sparhawk said. “Like ’oh, why don’t we just print it up?’ … And then after you put your own stuff out, you’re like, ‘that wasn’t so bad, I should put my friends’ stuff out, too’ And so that’s how that starts.”

From 2002 to 2007, Chair Kickers’ put out works by If Thousands, Haley Bonar, the Keep Aways and other Duluth artists, as well a few from outside the area.

The third Black-eyed Snakes album in 2018 is the most recent Chair Kickers’ release. It’s numbered CKM020, but, like Lindquist, Sparhawk struggled with record-label math.

“I think it actually should be number 21,” he said. “I put out a Cars & Trucks record for number 20 and I think I forgot or I just thought ’well, I doubt I put out 20 records, so I’ll just go with 20. Sure enough, the national registry people were like, ‘uh, there’s already a record registered under this catalog number.’”

Also true to DIY music standards, the label name varies at times, sometimes rendered as “Chairkickers’ Music” and also “Chairkickers’ Union Music.”

Despite Sparhawk’s general success in the music industry, running a small label was more about art than pecuniary rewards.

“It was hard,” he said. “It never really made its money. You know, I mean, the cost of getting something manufactured, when a minimum order is like a thousand and you end up selling maybe a couple hundred of them.”

Sparhawk said he knew early on that his label wouldn’t be profitable, but he thought the losses could be minimal.

“You’re doing this because you love music, and you want people to hear this record,” he said. “It’s probably gonna cost you some money to do that. And if you put 10 or 20 of those suckers out there you’ve lost a couple thousand bucks and it starts to get real.”

Eventually, Sparhawk decided he didn’t have enough time to work on the business part of running a label. Though Chair Kickers’ is technically still active, the Black-eyed Snakes’ Seven Horses has been the only release in the past decade.

“I remember getting to the point where I realized I can’t keep putting stuff out,” Sparhawk said. “I don’t really have the structure or know-how to navigate the way the business is changing, the way the internet is changing, the tricks of getting something talked about. … I remember just thinking, well, I’ve got a band, I gotta write music, I’m on tour all the time, I have a family, I need to pick and choose battles here. So I just gravitated toward putting less and less out.”

A Vortex of Pain

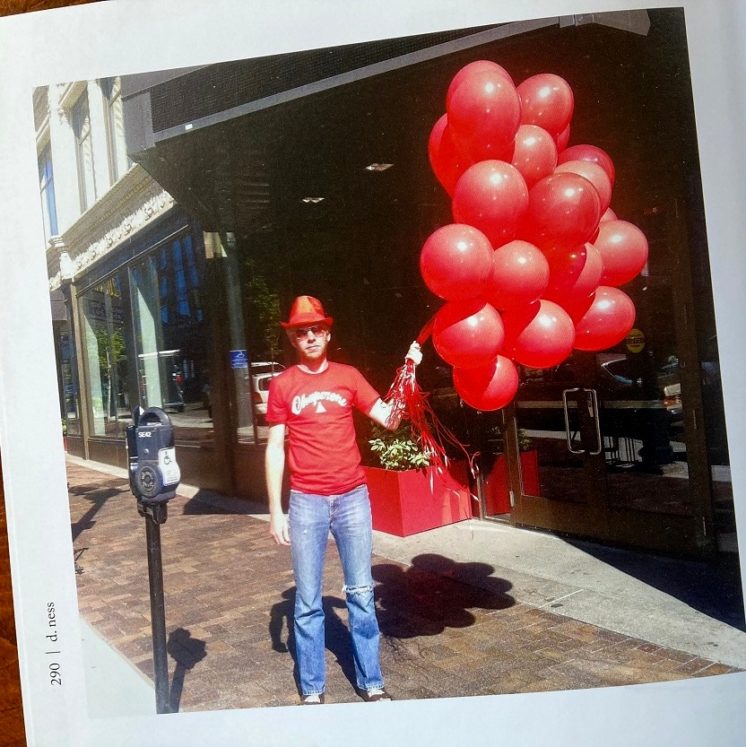

As Sparhawk and Lindquist drifted out of the Duluth record business, a new entrepreneur with grander visions stepped forward. Bob Monahan launched Chaperone Records in 2012. Having just graduated from Lake Superior College, he decided to dive headlong into entrepreneurism.

“The first meeting was between me and I think five fellow Duluth art and music scenesters who were friends of mine,” Monahan said. “That was the inception, was everybody basically agreeing that this was going to be cool. And we’re gonna make it a real thing.”

Monahan’s vision was to create a label that kept a close pace with Shaky Ray in the number of releases, rivaled Chair Kickers’ in the quality of music and promoted the local scene like Spinout’s Duluth Does Dylan series.

“I think that I started with a big dream,” Monahan said. “Basically catapulting Duluth sort of into the next level of the Minnesota music stratosphere. Because I had that head of steam. I had that belief in the quality of music that was coming out of Duluth at that time. There was some really bona fide talent — not that there isn’t now — but it sure felt like we could take some of that show on the road.”

Monahan went big on promotion, style and flash, exhibited in the promo video above, released to unveil Chaperone to the world. The label got attention, but initial sales were underwhelming.

“I think there was a little while where I thought this was going to be easy,” he said. “You know, that money was going to kind of come rolling in. … We had no idea what commercial success even looked like, much less tasted like.”

Things improved with Chaperone’s fifth project, a rerelease of Charlie Parr’s 2004 album King Earl.

“It was an honor to work with Charlie in that capacity, even though that record had been put out years before,” Monahan said. “It definitely felt substantial. I think that record was our first 500 run — it was a double 10-inch vinyl.”

But despite the marketing, the college radio campaigns, the hard work and belief in the music, overall album sales never matched expectations. Two of Duluth’s hottest new acts at the time — Red Mountain and Southwire — both put out albums on Chaperone that were raved about by music fans but were not hot sellers.

“The Southwire album definitely had this sort of naiveté-laced ‘holy shit, what’s gonna happen with this? How big could this record get?’ But very, very few of those records ever found more than a toehold in the market,” Monahan said. “They all had some kind of buzz … but the ones we put out with Charlie Parr and Retribution Gospel Choir — the more established artists — were the ones that actually did well.”

While Lindquist spent as little money as possible at Shaky Ray in order to keep putting out more and more music, Monahan considered Chaperone albums to be investments, though the possibility for payout was limited.

“Shaky Ray was punk rock as fuck,” Monahan said. “With Chaperone, we were touting ourselves as a boutique record label. And we wanted everything to basically sparkle and pop with sort of that impeccable handmade quality. … We were dedicated to vinyl from the beginning, and we were dedicated to hand screenprinting all the packaging and all that stuff. … The releases themselves were just beautiful … they were just these specimens … detailed quality from the recording and the mastering right down to the slip covers and the stickers. That’s what we were going for.”

Was it worth it?

“The easy answer is probably not,” Monahan said. “I learned that it takes a tremendous amount of money. When you really want to do something right and get a kickass recording … I mean, that was one of the things that maybe I didn’t have going for me was that I just was super biased about these recordings. I felt like everything we put out was like, you know, fucking gold.”

Monahan remains proud of the catalog of albums, and said he got a kick out of pretending to be a record-label bigshot at a few industry events, but ultimately he came to learn the combination of things that needed to fall into place for success were too elusive.

“I think most would agree that the music (industry) is kind of a vortex of pain,” he said. “It’s not necessarily about who is the most talented. It has a lot to do with a lot of other factors … marketability and who you know and who you may have paid, you know, and how to get in front of the right people.”

While Monahan was running Chaperone, he was simultaneously working to start a nightclub. The Red Herring Lounge opened in 2014, and as that operation ramped up, Chaperone began to wind down.

“It was kind of a very, very short-lived full-time job,” Monahan said of Chaperone. “The Herring pretty much took over my life … so what happened is Chaperone basically turned into a warehouse for records, and they were there when people needed them.”

Monahan closed the Red Herring in 2019 and, before moving out of the building at the end of the year, gave the remaining stock of Chaperone products to the artists. By then, seven years had passed since Chaperone launched, but the label’s releases were confined to the years 2012 to 2015.

The music business behind him, Monahan is now a hospitality entrepreneur, having opened Hostel du Nord in 2018.

Nelson sold his share of Fitger’s Brewhouse and related enterprises to his longtime business partner Rod Raymond in 2015 and started new businesses in Superior, opening the Cedar Lounge in 2016 and Earth Rider Brewing in 2017.

Mark Lindquist in his living room during the recording session for the compilation album “Let’s Get Filthy with Slim Goodbuzz,” June 21, 2003. (Photo by Paul Lundgren)

The Soft Death of the Hard Copy

How did it end for Shaky Ray? Lindquist moved from Duluth to Baxter in 2012, and though he continued recording and releasing his own music, he felt the Shaky Ray era had concluded.

“Not being in Duluth and not having the connection with anybody who maybe would be interested in Shaky Ray Records as much, I kind of switched over to BaxTrax Records,” he said, referring to the label name he uses to occasionally release his latest music.

These days, Lindquist is a music teacher and basketball coach at Central Lakes College. He’s also advisor to the college’s audio club, which released a compilation album at the end of 2020 featuring a variety of northern Minnesota musicians, some of which are artists who appeared on the Shaky Ray label two decades ago.

Chair Kickers’ and Spinout live on in a limited sense, but Duluth might never again see an ambitious multi-artist record label.

“I’m not sure it’s needed,” Lindquist said. When he launched Shaky Ray in the mid 1990s, he felt there was no other way for local music to get exposure. Bands could put songs on the internet at the time, but there wasn’t really an online platform for new artists to get attention. MySpace and YouTube arrived in 2005. Bandcamp launched in 2008.

But the internet wasn’t the only factor.

“It was harder to make things,” Lindquist said. “For a while, CDs were more expensive than records to make. But whatever, you know, money … you could save by collectively being on a label. … That kind of helped everybody out in those days. I don’t even think you need the record label now, you just do it yourself.”

So whether the artist is working alone or with a small label, it’s always a sort of DIY thing. But for a time, it suited Lindquist’s personality to bring artists together.

“I think you kind of have to be interested in archiving and documenting and putting together a body of work that doesn’t include your own,” he said about running a label. “And I was always interested in that.”

And there were benefits to having a party house in Duluth’s East Hillside where artists could get together and plan out projects.

Twenty-year-old Shaky Ray Records T-shirts adorn the rafters at the Perfect Duluth Day headquarters. The lower right image shows a printer error, rendering the band name Giljunko into what seems like the name of a person, Gil Junko. (Photos by Paul Lundgren)

“A lot of things happened at those Shaky Ray parties where musicians would get together, and there were writers and artists from different magazines at those parties,” Lindquist said. “So if you kind of got attached to that label, it was a networking thing. And maybe some of the things that you didn’t know how to do, I could find somebody who knew how to do it. And bands that maybe needed an artistic direction … Charlie Parr said he didn’t know how to make an album cover. I’d comment that, ‘hey Sarah Heimer is really good, if you want to use her to make an album cover.’ So I could put people together.”

Factoring out his labor, Lindquist thinks Shaky Ray basically broke even during its run. Certain albums sold well, meaning around 500 copies. Discs like Parr’s Criminals and Sinners, Father Hennepin’s Crooked with Gin, and Lindquist’s own best-selling creative work — the Giljunko album Gaspump Graveyard — offset other albums that lost money.

“It was maybe like $500 total to put out (a run of) 100 or 50 CDs,” he said. “We’d make that money back and move on to the next project.”

With most projects, Lindquist was spared the financial losses by making them sort of limited edition.

“My selling point was that there are only 100 of these in existence, you better buy them now,” he said.

As the industry shifts and independent music stores get scarcer, it could be even more difficult for small-time artists to sell their albums.

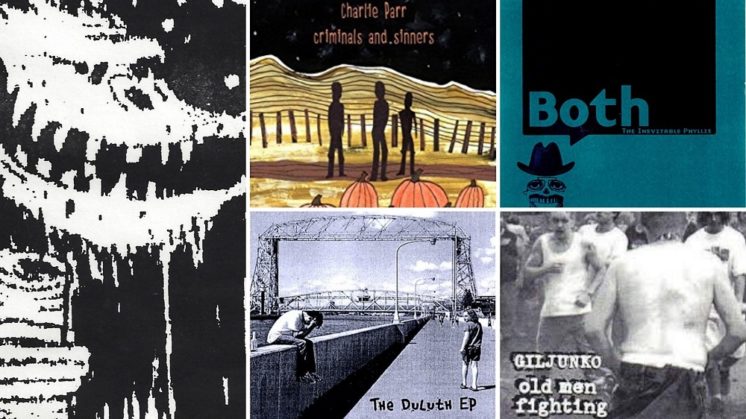

Cover art images from random selections of the Shaky Ray Records catalog, clockwise from left: Giljunko’s “1996-2002,” Charlie Parr’s “Criminals and Sinners,” Both’s “The Inevitable Phyllis,” Giljunko’s “Old Men Fighting” EP and Vinnie and the Stardusters’ “The Duluth EP.”

“Duluth is lucky to have the Electric Fetus,” Lindquist said. “They would let us sell stuff there. Go to a town that doesn’t have a store like that and find out what they say when you want to put your CDs in Target. They will tell you that it’s illegal.”

In true DIY punk-rock form, Shaky Ray skipped over little things like bar codes, copyright licensure and parental advisory labels. It wasn’t even a registered business, though Lindquist said he did pay taxes on the income.

“It wasn’t much,” he said. “During my entire existence running Shaky Ray I lived below the United States poverty line. I did my own taxes and I wrote a check to make sure I wouldn’t get in trouble for selling CDs and having a recording studio in my basement.”

Sparhawk said the way the industry mutates and the fickle tastes of listeners is just too challenging for a small label to keep adjusting, even if the goal might be to just sell 100 records.

“Just, in general, people don’t buy hard copies of stuff anymore,” he said. “That market has really, really declined. There’s sort of this niche for people who love vinyl, and they love going to record stores and, you know, there’s always going to be that crowd, but it’s just not as big as it was before. And it just doesn’t have as many opportunities and holes for people to jump in and try it.”

Nelson concurs.

“The business has changed so much,” he said. “Since I was trying to do much with it, it’s changed again. I know it’s a real struggle to get paid for your music — you gotta have so many clicks I guess — it’s just … I wish everybody luck.”

The Nostalgia and Music Live On

The struggle of deciding whether to go big or go punk with a label inevitably leads to both regrets and fond memories either way. Making a big investment wasn’t an option for Lindquist, but he nonetheless wishes he had slowed down and put more attention to detail into a few releases.

“I jumped from project to project really quick,” he said. “And I really regret that. I would literally put out a CD and two weeks later I was kind of ready to put out another by a brand new act I was all excited about. … A lot of those things could have used more time. … I was in a race where I was going to die or something and I just had to put it out before I died and then I realized I could have taken my time and made it sound better.”

Still, Lindquist is easily excited when he talks about the Shaky Ray days and the music that came out of it.

“I get very nostalgic for that time,” he said. “Some of those guys and gals are unbelievable songwriters and unbelievable performers. And I can’t explain that to people I talk to nowadays. They have no idea what I mean. It was off the charts and I don’t know if that was just a one-time thing in Duluth. I doubt it. But, you know, let’s say I worked with 12 to 20 different artists in a year — almost all of them were uniquely talented … and I got to host them at my house all the time.”

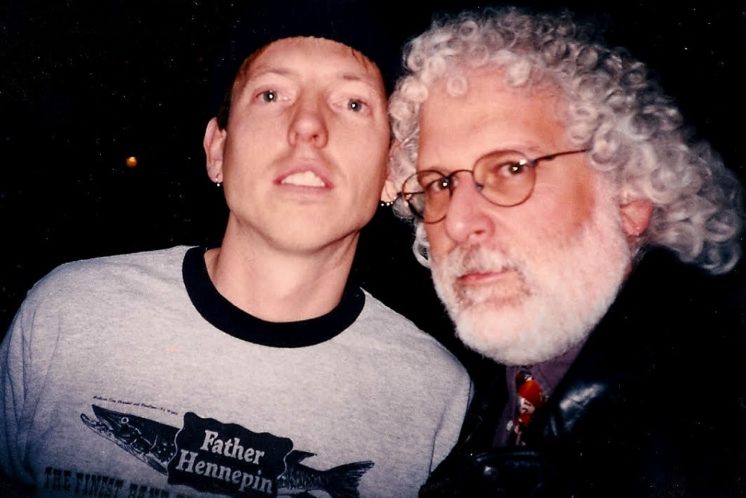

Brian Joens, Erik Koskinen, Tim Nelson, Bernie Larsen and Glade Sowards at Fitger’s Brewhouse, December 1999.

Nelson also has fond memories of the camaraderie of Spinout artists working together to promote their music.

“The big thing we were doing back then is we were like this little co-op,” he said. “We’d tour together. So even when Bernie was in California, we’d come in with a couple of musicians, and then (Nelson’s band in the 1990s) Gild would jump in as the backing band, and we’d go out with Erik Koskinen. And then we’d have, you know, three bands in one, basically, and we’d go around to these little towns and tour around our area. You know, it was kind of a traveling Spinout show. And that was pretty cool. And that’s one thing that I look back on as pretty awesome.”

Sparhawk warned Monahan when Chaperone was starting: “Be careful. Don’t spend any money that you don’t want to lose.” But money is just money, and an album that captures a moment of great artistic expression is no waste of funds.

“The Southwire record is phenomenal,” Sparhawk said. “I’m so glad those records were made. You know, you do it because you love music, not because it’s gonna turn around and make anything.”

Recommended Links:

Leave a Comment

Only registered members can post a comment , Login / Register Here

2 Comments

Chris Godsey

about 3 years agoPaul Lundgren

about 3 years ago