My Favorite Writers/Biggest Influences: Stanislaw Lem

Stanislaw Lem was born in 1921 in Lwow, Poland which is now Lviv, Ukraine. He died in 2006 in Krakow, Poland.

He was a Jew who survived the Holocaust, which in Poland was bracketed by two Soviet invasions. He went on to become one of the greatest science fiction writers in the world. His best-known work (in America) is the novella “Solaris,” which became a 2002 film directed by Steven Soderbergh and starring George Clooney. Lem sold more than 40 million books worldwide.

Surviving the Holocaust

In his 1986 essay “Reflections on my Life,” Lem included many details about the Nazi occupation of Poland, which I include here in his own words. It is a personal, immediate, and shocking record: “I knew that my ancestors were Jews, but I knew nothing at all of the Mosaic faith and, regrettably, nothing at all of Jewish culture. So it was, strictly speaking, only the Nazi legislation that brought home to me the realization that I had Jewish blood in my veins. We succeeded in evading imprisonment in the ghetto, however. With false papers, my parents and I survived that ordeal …. My uncle, my mother’s brother … a physician … was murdered two days after the Wehrmacht marched into Lvov. At that time, several non-Jewish Poles were also killed – mostly university professors – and … one of the best-known Polish writers. They were taken from their apartments during the night and shot …. I resembled more a hunted animal than a thinking human being …. As far as I know, all, or nearly all, of (my friends in the ghetto) were transported to the gas chambers of Belzec in the fall of 1942 …. (and) mentally ill persons (and many others) were indeed murdered by the thousands.”

Working as a welder at a German company, Lem had access to a depot used by the German Air Force. In this capacity he risked his life smuggling guns, ammo, and radios from the Luftwaffe to the Polish resistance, “which I considered to be my duty.” According to this article in Wired, “his cover was blown, (and) he went into hiding, resurfacing when the Red army arrived in 1944.”

How Occupied Poland Influenced his Writing

In “Reflections on my Life,” Lem described how his experiences in Poland formed his subsequent science fiction writing career.

Poland’s constant paradigm shifts germinated his sci-fi writer’s craft of world-building: “I have lived in radically different social systems. Not only have I experienced the huge differences in … prewar (capitalist) Poland, the Pax Sovietica in the years 1939-41, the German occupation, the return of the Red Army, and the postwar years in a quite different Poland, but at the same time I have also come to understand the fragility that all systems have in common, and I have learned how human beings behave under extreme conditions.”

The fact that he wrote science-fiction, and created new story forms (like reviews of fictional books etc.), he attributed in part to living through the Holocaust: “Those days (in a Poland occupied by the Germans) have pulverized and exploded all narrative conventions that had previously been used in literature. The unfathomable futility of human life under the sway of mass murder cannot be conveyed by literary techniques in which individuals or small groups of persons form the core of the narrative … I do not know, of course, whether this sort of narrative inadequacy was the reason that I started writing science fiction, but I suppose … that I began writing science fiction because it deals with human beings as a species.”

Regarding Lem’s cynicism, his biting satire, and his dry, black humor, one is almost tempted to characterize him as a bitter nihilist. He could not be blamed if this were so. But according to him, the truth is more nuanced, and even contains a little bit of optimism: “I am a disenchanted reformer of the world … I am not yet a despairing reformer of the world. For I do not believe that humanity is for all times a hopeless and incurable case …. I have written many books … to be found in the provinces of the humorous … As is well known, the great humorists were people who had been driven to despair and anger by the conduct of humanity. In this respect, I am one of those people.”

World-Famous Science Fiction Writer

After World War II ended, Poland was re-occupied by the Soviets. Lem’s family had lost everything. Before the war, his father had been a rich doctor and the family had lived in a large house, with a French governess, and “no end of toys.” After the war, they lived in a single room, and his elderly father could not afford to open his own practice again. Lem discovered he could help financially by selling short stories, poems, and novellas to weekly magazines. By the early 1950s, after getting a job as a research assistant for a scientific organization, he began writing the science fiction novels which made him world famous and even wealthy. Although he had limited success in the United States, he achieved rock-star status in Europe and Russia, selling over 40 million books.

Among those books was the novella “Solaris.” I have not read it, but I have seen both big-screen adaptations. Lem didn’t like either of them! But they are similar enough to each other that a triangulated picture of the book becomes clear in its broad outlines, obviously a visionary story. A 2004 poll of scientists named the three-hour, 1972 Russian Solaris film (dir. by Tarkovsky) as the 5th best science fiction film of all time (after Blade Runner, “2001: A Space Odyssey,” the first two Star Wars movies [episodes 4&5 tied], and Alien).

There is also the 90-minute, 2002 American version directed by Soderbergh, which the “Time Out Film Guide” called superior to the 1972 version.

It’s an apples-to-oranges comparison; each did a great job on one of Lem’s persistent ideas: that “first contact” with an alien intelligence is not likely to go well. Lem derided American sci-fi’s simplistic construction of first-contact scenarios as either “we win” or “they win.” He hit a rich vein when he explored ways it could go wrong. He argued that our anthropomorphic idea of intelligence is very narrow, and that we may not understand alien intelligence at all. This idea has gained credence over time (as in recent films like 2016’s “The Arrival” and 2018’s “Annihilation”), but when Lem began exploring it, it ran contrary to the dominant sci-fi of the day.

Like Jorge Luis Borges (writer #1 in this series), Lem got into writing short pieces that simply introduced ideas. Setting, characterization, and plot were just window dressing around a central concept.

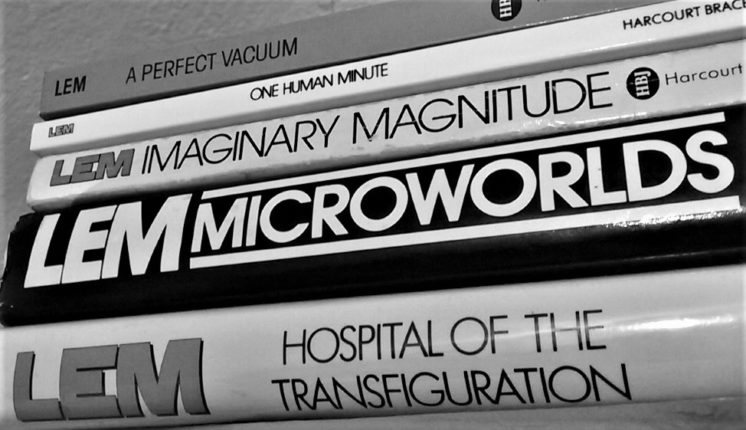

For instance, Lem wrote three books that consist entirely of reviews of books that do not exist. This gave him a way to play with story form while presenting overviews of his ideas. The form almost completely ignores character development — except possibly for the oblique character development of the reviewer — and ignores conventional plot structure. He admitted that a couple classical writers had beaten him to this concept. And, of modern writers contemporary with him, it was Borges who had preceded him with a review of a fictional book. In the intro to A Perfect Vacuum, Lem asserts that while he did not invent the form, his innovation was to write whole anthologies of the fake reviews, establishing many variations.

In a similar vein to imaginary book reviews, Lem also wrote a book of introductions to books that don’t exist, called Imaginary Magnitude. This is one of my favorite books. His introduction is, hilariously, about introductions. The book could be considered a novel; the pieces refer to each other in glancing but chronological ways, building an alternate future timeline of technological conundrums. One piece introduces a book of literature written by AIs, including new literatures that humans cannot understand. The final piece, Golem XIV, is a novella-length introduction to a book of lectures from an AI that has developed God-like intelligence.

Golem XIV is astounding in the way it describes an intelligence unreachable by humanity. I regard it as a masterpiece, akin to Solaris in that each probes Lem’s central concern that other intelligences may be incomprehensible.

Reviewing Imaginary Magnitudes for the New York Times, Philip Jose Farmer (one of the writers who threatened to quit the American Science Fiction Association if Lem were offered a membership [see below]) nonetheless referred to Lem as “a science-fiction Bach.” The book displays the technology of an alternate future in incredible detail, done largely without characters or plots. It is indeed a new form of literature, a masterpiece of world-building, and often very funny. Like when the AI, Golem XIV, says despairingly of humanity: “Man is a deficient creature … Evolution did what it could, although what little it did, it did poorly.”

Lem vs. American Sci-Fi

For much of Lem’s career, American science fiction was difficult to come by in Poland. Lem’s sci-fi developed in the hermetically-sealed isolation of state censorship. As the Wired article put it: “He assumed that he had colleagues in America and that, like him, they were exploring the nature of technological progress and its effects on civilization …. When Lem had a chance to catch up with what his Western counterparts were up to, he was horrified. Science fiction, he discovered, consisted mainly of fantasy and adventure without a shred of seriousness. Lem set out to reform the genre. In the ’60s and ’70s, he wrote a series of essays lambasting what he considered the intellectual poverty of most science fiction, taking even its most famous authors to task for their technical ignorance, literary clumsiness, and sociological naïveté. He filled dozens of pages of academic journals such as Science Fiction Studies with dense arguments of how sci-fi was failing to meet its potential.” (Many of these essays are collected in Microworlds: Writings on Science Fiction and Fantasy.)

Unaware of this criticism, the American Science Fiction Writers Association (ASFA) granted Lem an honorary membership in 1973. Then, when his opinions were brought to light, his honorary membership was revoked in a vote where 70% of the membership voted against him. The so-called “Lem Affair” caused tremors through the American sci-fi community. Some members of the ASFA threatened to quit if Lem were granted a membership; others (Ursula K. Le Guin prominent among them) did quit because Lem was denied a membership. The ASFA tried offering it to him again, which he refused, saying later, “to me the opinion of morons is worth exactly nothing.”

Philip K. Dick vs. Lem

The only science fiction writer Lem respected was Philip K. Dick. In Microworlds, Lem wrote an essay praising him, while also backhanding most other sci-fi writers with the title alone: “Philip K. Dick: A Visionary Among the Charlatans.” Dick’s stories focused on the nature of reality, which to Lem demonstrated a philosophical depth and seriousness. Both writers wrote stories that made the reader question reality.

I almost put Philip K. Dick into this essay series as one of my favorite writers, but I’ve simply read too little of him. I remember his prose as being fairly chatty which I tend to dislike – but the whole VALIS idea blew me away – (Dick’s drug-fueled delusion that his mind was being intersected with an alien satellite AI). It was so far out — almost a living idea leaking from book to book, mysterious and conspiratorial. Nominally pill-driven, Dick was sinking into schizophrenia, and believed he was at the center of a cosmic conspiracy. In a way, that’s why Lem liked the work: Philip K. Dick didn’t just write good stories, he presented genuine ontological quandaries. The fact that Dick was crazy didn’t affect the strength of his work – in fact, it improved it. (And Dick was funny. Lem is perhaps not known for being funny because he’s so brainy and deep – Solaris is not funny — but much of his other work is sheer comedy.)

Although Lem was praising him, Dick was so high and crazy that he wrote a letter to the FBI accusing him of being not just a Soviet spy, but an entire communist propaganda committee. According to Dick, Lem didn’t actually exist — except as a figurehead for the purposes of infiltrating American sci-fi.

Dick apparently later recanted, and advocated for Lem at the ASFA during the latter part of the “Lem Affair.”

Lem vs. Borges

The thing about Lem is that his prose and ideas are a lot like Borges – they could almost be the same person in disguise, if Borges wrote “science fiction” instead of “fantastic fiction.” The Los Angeles Review of Books called Lem’s reviews of fictional books “Borgesian,” and the similarity is undeniable. Lem and Borges independently preferred to write short fiction, because simply conveying ideas was their overriding concern. They are masters of a type of short story written in similar prose, what you might call logical parables — glimpses of parallel worlds with such precision that each contains its own opposite. (Italo Calvino [writer #5 in this series] also wrote such parables.)

What’s funny about the connection to Borges is that Lem wrote an essay more or less tearing Borges down (“Unitas Oppositorium: The Prose of Jorge Luis Borges”). Lem essentially called him a one-trick pony, albeit one whose trick is amazing (the construction of “brilliant paradoxes”).

But Lem used the same trick. I think the essay reads very much like Lem is saying, “Borges is a very great genius, but since he didn’t do what I did, I am the greater genius.” In my essay on Borges, I unrepentantly argue Borges is a world-class genius; I am also arguing here that Lem is one too. I think both are above reproach. But if any critic has the authority to complain that Borges didn’t invent new forms – (essentially, that he didn’t write science fiction) – let that critic be Lem. This amounts to a feud between intellectual giants, as far beyond the reach of mortals as the god-like Solaris, or Golem XIV. Lem vs. Borges is like King Kong vs. Godzilla – a spectacular disagreement.

Other installments of this series:

All my essay series here.

Recommended Links:

Leave a Comment

Only registered members can post a comment , Login / Register Here

No Comments