My Favorite Writers/Biggest Influences: Jorge Luis Borges

I read, and re-read, the same few authors. I find them impossible to put down. Here are my favorites, the biggest influences on my own writing — and why.

Jorge Luis Borges was born in Argentina in 1899.

He died in Switzerland in 1986.

Borges’ mother was from a Spanish family that settled in Uruguay, and then moved to Argentina to take part in the Argentinian War of Independence.

Borges’ father was also Argentinian, of Spanish and Paraguayan descent – but he spoke English around the house because his mother – Borges’ grandmother — was English.

Borges was a bookish child and somewhat ashamed of it, because his family was, in general, full of passionate revolutionaries. That said, his father was a bilingual book collector, who (according to Borges) “tried to be a writer and failed.”

Blindness ran in the family and his father went blind. Borges knew his own fate would be to go blind eventually as well.

Borges’ little sister, Norah Borges, grew up to become a notable surrealist/cubist painter in the so-called “Florida School,” which was centered in a tea room on Florida Street, Buenos Aires. Before coming into her own fame, she labored long in her more famous brother’s shadow. Borges wrote about their childhood: “In all of our games she was always el caudillo [the leader], I the slow, timid, submissive one. She climbed to the top of the roof, traipsed through the trees, and I followed along with more fear than enthusiasm.”

To treat his advancing blindness, Borges’ father had the bad luck to move the family to Europe in 1914. Among other things, this meant they couldn’t leave when they wanted because they were delayed by World War I.

Stuck in Europe, Borges learned additional languages including French and German. He translated Oscar Wilde from English to Spanish at age nine. He read Shakespeare at age 12. He said later that his father’s library was his favorite thing. Another example of Borges’ skill as a polyglot is that he not only grew fluent in English but in Old English; not only German but Middle German, etc.

When they moved back to Argentina in 1921, he submitted a story to a surrealist magazine, prefiguring his writing career (somewhat like Italo Calvino years later [writer #5 in this series]) as a teller of conceptual fables.

In 1935, Borges published a book of short stories called “A Universal History of Infamy,” arguably the first book in the “Magical Realist” movement of mostly South American writers. This group included Gabriel Garcia Marquez, who blew up as part of the “Latin American Boom” of the 60s, a movement which Borges influenced strongly. Its rise cemented his status as an international giant of Literature.

In 1955, Borges gained a lifetime appointment as head of the Argentine national library, ironically going completely blind in that same year. Assistants, including his mother, read him the literature of the world in different languages. He wrote through dictation.

He had an encyclopedic knowledge of global history, literature, and philosophy. In 1967, nearing 70 years old, he gave six extemporaneous lectures on literature at Harvard with no notes, quoting classic literature and philosophy at great length from memory. I consider him a Socrates or a Homer. That his blindness is akin to Homer’s — and Milton’s — has not gone unnoticed.

One example of his supreme academic mind was his knowledge of the Odyssey. He could not read the original Greek. In the Harvard lectures he says, “I have no Greek,” and he sounds apologetic. Like he’s saying, “I’m sorry I cannot read The Odyssey in its original language, so, I read every translation in every other language instead.” He compared and analyzed all the different translations in his essay “The Homeric Versions.” As usual (as all great thinkers do), he turned the issue on its head, questioning whether the original text is as authoritative as any of the translations. The essay is fundamentally about the ways languages differ, and the different ways of seeing each represents. It is a question he was ideally suited to explore.

Borges is easy to read, even about complicated subjects. He effortlessly juggled the ideas of the world, based as he was in one of its great libraries.

Like Stanislaw Lem (writer #4 in this series), Borges eschewed writing novels in favor of shorter pieces. He felt the important thing was to present ideas, not to develop them over a book-length manuscript. That said, his short stories and his essays contain infinities. These traits liken his stories to the work of Calvino, and to J.G. Ballard’s most electrifying short stories (writer #3 in this series). It has been suggested that Borges’ very blindness aided the richness of his interior world, and his precise construction of labyrinthine ideas.

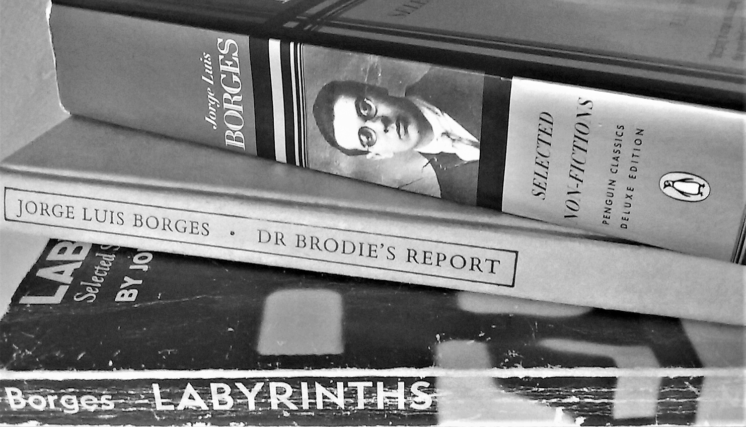

I was introduced to Borges’ fiction in college when I was loaned the short story collection Labyrinths. I have also read The Aleph and Other Stories, and the short story collection Dr. Brodie’s Report which Borges wrote late in life.

In the wonderful preface to Dr. Brodie’s Report, Borges gives some insight into his writing process and philosophy, in a passage (which I have condensed with copious ellipses, forgive me) which is typical of his prose: “Kipling’s last stories were no less tormented and mazelike than the stories of Kafka or Henry James, which they doubtless surpass; but in 1885 … the young Kipling began a series of brief tales, written in a straightforward manner … several of them… are laconic masterpieces. It occurred to me that what was conceived and carried out by a young man of genius might modestly be attempted by a man on the borders of old age who knows his craft … I have done my best … to write straightforward stories. I do not dare state that they are simple; there isn’t anywhere on earth a single page or single word that is, since each thing implies the universe, whose most obvious trait is complexity …. For many years, I thought it might be given me to achieve a good page by means of variations and novelties; now, having passed seventy, I believe I have found my own voice …. My now advanced age has taught me to resign myself to being Borges.”

I am most pleased to own Collected Non-Fictions, a comprehensive collection of nearly every essay he wrote over the course of his life. The ideas he explored have had consequential impacts on not just writing and literary criticism, but on philosophy and history. Non-Fictions is enormously brainy. I will admit it hurts to read sometimes, if only because he references so many authors, philosophers, schools of thought, and historical events. But his language is economical, incisive, and so enjoyable. Every page is full of marvelous phrases and aphorisms. The book is virtually a master class in literature, history, and philosophy. It has enriched my life immensely.

More in My Favorite Writers essay series:

William S. Burroughs, my second installment.

Third installment J.G. Ballard here.

Fourth installment Stanislaw Lem here.

Fifth installment Italo Calvino here.

All my essay series here.

Recommended Links:

Leave a Comment

Only registered members can post a comment , Login / Register Here

No Comments