The History of Cloquet, Pierre the Pantsless Voyageur and Duluth’s Missing Vermeer

Excerpts from Scions of Cloquet by Jean-Michel Cloquet (1946, out of print)

Excerpts from Scions of Cloquet by Jean-Michel Cloquet (1946, out of print)

“In 1820, when he was 17 years old, the Frenchman Pierre Cloquet boarded a packet ship in Le Havre and sailed across the Atlantic Ocean. He was trying to escape his father, like many of us try to do, perhaps all of us. He just wanted a little peace and quiet. By a certain measure, he found it in the territory eventually known as Minnesota. Pierre (or Grandpère Cloquet as my brother and I refer to him) became a legendary voyageur and fur trader 20 miles southwest of Duluth, trapping, hunting, and occasionally bear-wrestling. Over two decades of working for the American Fur Company, he built his own trading post where metal tools shipped in and beaver pelts shipped out. He gradually adopted native dress, and he married into a Black-Ojibwe family out of Michigan, sought-after guides and translators. And, right around the collapse of the beaver pelt industry in 1843, he inadvertently founded the town of Cloquet.

“Three families had mills in that area: the Johnsons, the Nelsons, and the Shaws. Settlements gathered around the mills, which became known respectively as Johnsontown, Nelsontown, and Shawtown. And they were about as far apart as they were close together. There was a waterfall with sharp rocks nearby, so folks referred to the three settlements as Knife Falls.

Knife Falls area circa 1880 (Carlton County Historical Society)

“Pierre met his wife at Knife Falls one late summer. She watched from behind a boulder as he fished. He knew she was there, but acted like he didn’t. She knew he was there, and acted like she did. First he used a minnow and caught a small fish. Then he used that fish and caught a 24-inch long, 75-pound snapping turtle king. For hours after his cork dived, all afternoon in fact, she watched as Grandpère dueled the furious snapper. He raised it from its deep pool like conjuring a demon. Hauling it onto the shallow bank, tiring now, he grabbed its tail and flipped it onto its back.

“At last she approached. She helped him remove the hook from its vociferous mouth, gingerly taking his pliers and doing it herself.

“Hungry, swamped in sweat, he sat and mopped his brow a moment while she kept the turtle on its back. Grandpère let himself imagine the hearty turtle soup he would share with this woman: onions, celery, carrots, potatoes, spinach, mushrooms, thyme … he loved how the mushrooms mixed with the turtle fat to become a fifth taste he couldn’t describe…

“Suddenly she raised to her full height. A six-foot tall goddess in deerskin, she lifted the turtle by its shell with both hands, holding it from her body as the sun careened toward the horizon. The snapper was not happy with the situation. Clawing the air, hissing and growling, the animal reflected her own powerful energies.

“She looked Pierre in the eye and said, in either English, French, or Ojibwe, ‘My name is Sound of Falling Stars. And I regret to inform you, monsieur, that I am Turtle Clan.’ His jaw fell open. Then she threw his dinner back in the river.

“The river was thereafter called the Cloquet River, a community joke at Pierre’s expense about having his dinner denied by a woman he married anyway. He’d made the mistake of telling the story to one person, and from there it spread at practically 20 miles per hour. You can’t outrun a story that good. Forgotten now, at one time it was considered so hilarious that in 1843, Knife Falls voted to re-name itself after the Cloquet River. And that is how the town of Cloquet got its name, and that is why we say Grandpère inadvertently founded it.

“Then the beaver pelt business dried up. But they stayed out there and made do as Cloquet grew around them; in addition to lesser-value furs, they peddled homemade mosquito repellent made of bear grease in little tins. Grandpère died in his sleep at 94 in 1898. He was followed by Grandmother Sound of Falling Stars, who turned 87 two years later and dropped dead in the garden patch. They are buried side-by-side in Cloquet. They had outlived their son, Henri Cloquet, by several years.”

Henri Enragé Cloquet

“Our father was born Henri Sound of Falling Stars Cloquet in 1843, around the time Knife Falls became Cloquet. He couldn’t stand the town jokes about his father not wearing the pants in the family. Referring to this, some people used the term ‘the pantsless voyageur.’ The belittling moniker spread through the forest settlements and logging camps as far as Two Harbors, becoming a tall tale like Paul Bunyan. It wasn’t even that true. But the name Cloquet had become synonymous with ‘getting your turtle thrown back in the river,’ and that part was true.

“Henri was not a tall man, for which his parents blamed each other’s mothers. Resenting his father and his mother, Henri left home in 1860 at age 17, passing for white. And if anyone ever teased him about turtles or pants he punched them in the nose.

“Henri tried his hand at being a lumberjack but he punched too many people. So he moved to the big city — Duluth — to work as a more anonymous laborer. In 1863, at age 20, he joined the Union Army and saw action with the Hillside Irregulars of the Minnesota First. At the Battle of Mine Run, he singlehandedly killed six Confederates in their trench using nothing but his fists, a rusty bayonet, and one shot from his Colt .44. This action earned him the nom de guerre Henri ‘Enragé’ Cloquet.

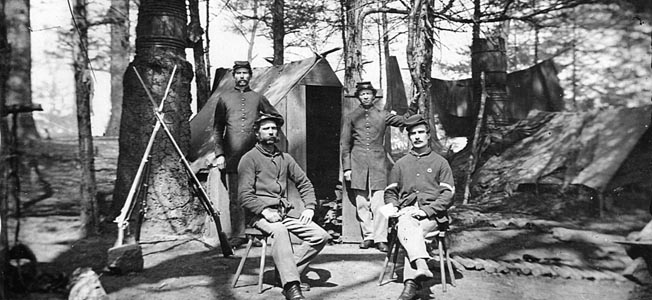

The Hillside Irregulars, Gettysburg, July 1863. Clockwise from upper right: Henri Enragé Cloquet, Old Babyface Bong, Buckminster Wilde aka John Buzzcock, Stanford Fancypants Nettleton (Minnesota Historical Society)

“After the Civil War, he found God, became an itinerant Jesuit missionary, and divided his time between Duluth and the Iron Range. He was known as a Duluth bachelor until he turned 50. He finally married our Swedish immigrant mother Astrid Stad, age 29, learning a fourth language (Swedish) in the process of converting her. We were born a year later at St. Mary’s in Duluth. But Mother heard a rumor that her supposed holy man had a second family on the range and that they were quite well off. Then she realized we were his second family.

“He disappeared in 1895 at age 52. Jacques and I were a year old. When we were five, Grandmother Sound of Falling Stars told us our father had probably been eaten by Protestants during that tough range winter. Others said Mother dumped his poisoned body in the scrub. She maintained until her dying day that ‘he just needs to come back home.’

“Mother retreated into Catholic mysticism. Once she told us she’d had a vision of God. ‘Where did you see Him?’ Jacques asked. She pointed to her head: ‘Here, child.’ She died of pneumonia in 1911. She was 47.”

The Cloquet Brothers and Duluth’s Lost Vermeer

“Growing up in Duluth was a wilderness adventure all its own that turned us into hardy spirits. My brother and I became the ‘Cloquet brothers’ in the early 1900s, the scions of Cloquet, colorfully adding to the region’s snow-and-lake culture as junior sportsmen.

“In 1912 we were 18 years old living at the Boat Club. Mother had not been dead a year. And I wanted to stay and he wanted to go.

“Jacques and I shook hands at the marina and parted ways, never to meet again. He set his solo sailboat to the wind and left to navigate the length of the Americas. He met Shackleton in 1914 at the ends of the Earth and spent half the Great War marooned on an ice floe. We know he was rescued but after that his trail goes cold.

“Meanwhile the war heated up. I shipped out to the front in 1917, tracing Grandpère’s path in reverse over the ocean, from America back to France. The Cloquets are distant cousins with the French exile Théophile Thoré-Bürger, the art critic who re-discovered Vermeer after the painter’s centuries of obscurity. In Europe I made contact with Thoré-Bürger’s nephew, Hercule, my fourth cousin thrice removed, and rescued one of his so-called ‘missing Vermeers’ from the Kaiser. ‘A Little Beach Near Delft’ returned with me to Duluth rolled up in my kit bag.

“A small painting like most of his work; this one is 24 inches by 18 inches. It is a rare landscape. Hercule handed it to me and hours later, he and his flat were obliterated in an artillery barrage like he’d feared. This also obliterated the provenance, but that never mattered to me. The canvas is an heirloom as far as I’m concerned, uniting two branches of our family through the image alone, which could be mistaken for a view from Duluth.

“The painting shows the sea from a beach dotted with bathers, while on the horizon a single white sailboat holds up the sky. I pretend it is Jacques returning. The bright water showcases the expensive natural ultramarine pigment characteristic of the master. A pearly light unifies the composition as if there is the faintest of mists. ‘Vermeer’ means ‘of the sea.’

“I have left it to my brother, if he should ever be heard from again. Rumors that he staged his own disappearance provoke me and I am unable to grieve. My will contains signs in our twin’s language only he will know, directing him to the painting I have hidden behind another painting, hanging somewhere in the Duluth city limits.”

Jean-Michel Cloquet died at 56 in Duluth during the blizzard of 1950, in an accident. His ashes were scattered in Lake Superior. The fate of his twin brother Jacques Cloquet remains unknown. The painting, if it is a Vermeer as claimed, has not been found. Current speculation is that it may reside in City Hall behind the portrait of 1940s Duluth Mayor George W. Johnson. Cloquet is now a bustling small city of nearly 13,000 people.

An index of Jim Richardson’s essays may be found here.

Recommended Links:

Leave a Comment

Only registered members can post a comment , Login / Register Here

1 Comment

eidsvolling

about 9 months ago